A new study from scientists at the University of Toronto and the Royal Ontario Museum reveals a clue into the origins of the mandibulate group of animals, found preserved in 508 million-year-old sedimentary rock of the Burgess Shale fossil site in BC’s Kootenays.

A new study from scientists at the University of Toronto and the Royal Ontario Museum reveals a clue into the origins of the mandibulate group of animals, found preserved in 508 million-year-old sedimentary rock of the Burgess Shale fossil site in BC’s Kootenays.

The largest and most diverse of creatures on Earth, the mandibulate clade includes insects, crustaceans and millipedes and is characterized by, you guessed it, their mandibular appendages near their mouths, used for defence as well as to grab, cut and crush their food.

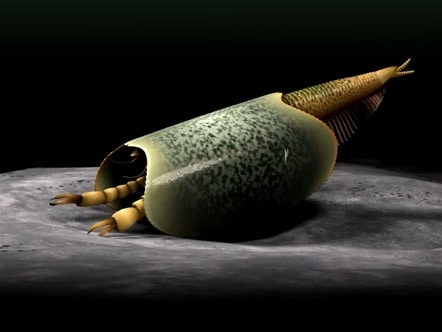

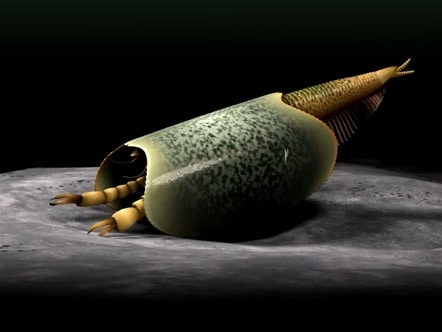

The newly-discovered species, named Tokummia Katalepsis, is no exception, with its own set of mandibles both serrated and claw-like. “The pincers of Tokummia are large, yet also delicate and complex, reminding us of the shape of a can opener, with their couple of terminal teeth on one claw, and the other claw being curved towards them,” said Cédric Aria, recent graduate of the Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology at U of T and now a post-doctoral researcher at the Nanjing Institute for Geology and Palaeontology in China.

Aria and colleagues have called the evolutionary history of arthropods (which include the mandibulates) “one of the greatest challenges in biology.”

“In spite of their colossal diversity today, the origin of mandibulates had largely remained a mystery,” said Cédric Aria. “Before now we’ve had only sparse hints at what the first arthropods with mandibles could have looked like, and no idea of what could have been the other key characteristics that triggered the unrivaled diversification of that group.”

Found near Marble Canyon in Kootenay National Park during a Royal Ontario Museum expedition, the Tokummia is named after Tokumm Creek with flows through Marble Canyon. The Burgess Shale region is world-famous for its soft-bodied preservation fossils. While fossilized bone and hard shell are usually all that scientists have to work with, the particular geological history at the Burgess Shale allows for special insight into the body parts of predominantly soft-tissued creatures like the Tokummia.

“One of the beauties of Marble Canyon and the Burgess Shale which this unit belongs to is the preservation of soft tissues,” says study co-author Jean-Bernard Caron, senior curator of invertebrate palaeontology at the Royal Ontario Museum, to Radio Canada International. “This animal is absolutely, stunningly well-preserved. You have to imagine that it is an animal that would have been entirely soft in the sense that there are no mineralized parts such as a shell or bones—of course, it’s an invertebrate. So, it’s really under very special conditions that the soft tissues of this animal got preserved.”

The fossils of the Burgess Shale come from the middle Cambrian period, a time marked as the “Cambrian Explosion,” when life forms went from simple- to complex, multi-cellular creatures. The mid-Cambrian period is also known for the separation of the supercontinent Rodinia into two parts, Gondwana, which would form much of modern-day Africa, Australia, South America and Antarctica and Laurentia, which now makes up parts of Europe and much of North America.

Earlier this year, Caron and colleagues published their findings on a wormlike species called Ovatiovermis, also from the Burgess Shale site. The detail of the creature’s preservation is remarkable, said Caron, who called it “one of the most beautiful fossils I’ve ever studied from the Burgess Shale.”

Below: Tokummia walkcycle

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Share

Share

Comment