Polio Lasted 50 Years. Will Coronavirus?

April 26, 2020 will mark the 66th anniversary of the massive polio vaccine trial on thousands of schoolchildren. Considering what is happening in the world right now, it is a good time to reflect on the challenges our predecessors faced not that long ago.

We are lucky enough to not give polio a second thought today, but every summer starting in 1916, and lasting four decades, a polio epidemic would appear.

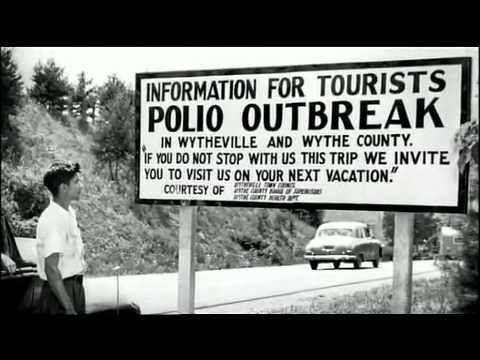

Each summer, cities would shut down public gathering areas like swimming pools and movie theatres. Since polio mostly affected children under five years of age, kids suspected of having it would be physically removed from playgrounds and their families sent to isolation in sanitariums.

Polio was horrific. American historian and journalist Richard Rhodes described it as a plague; “One day you had a headache and an hour later you were paralyzed,” he recalled. “How far the virus crept up your spine determined whether you could walk afterward or even breathe. Patients waited fearfully every summer to see if it would strike. One case turned up and then another. The count began to climb, the city closed the swimming pools and we all stayed home, cooped indoors, shunning other children. Summer seemed like winter then.”

Merely two months ago, we would have thought these measures of closing public spaces sounded extreme. But with the staggering number of polio cases each year drastic measures were necessary. Before the polio vaccine was available, it had been estimated that at its peak, polio paralyzed and killed up to half a million people every year.

American virologists Thomas Huckle Weller and Frederick Chapman Robbins, who was also a pediatrician, were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1954 for isolating the poliovirus. Their research was vital to Jonas Edward Salk, the virologist who engineered the first successful polio vaccine.

But theirs was not the first polio vaccine created.

That ‘honour’ goes to two separate research teams led by Dr. Maurice Brodie, a McGill University Faculty of Medicine graduate, and Dr. John Kolmer of Temple University in Philadelphia. Between the two research teams over 20,000 individuals including more than 10,000 children were used as test subjects.

In 1935 the researchers presented their results at the American Public Health Association’s annual meeting. The College of Physicians of Philadelphia noted that anger from fellow researchers ensued as “the tests proved a disaster [because] several [test] subjects died of polio, and many were paralyzed, made ill, or suffered allergic reactions to the vaccines.”

This outrage led to the cancellation of Brodie’s and Kolmer’s polio vaccine research projects.

In a world that can sometimes seem to be defined by greed, Salk decided to buck the trend and refused a patent for his polio vaccine. He believed it belonged to the world. From 1955 to 1962, the “world’s” polio vaccine reduced the cases of polio by 90 per cent.

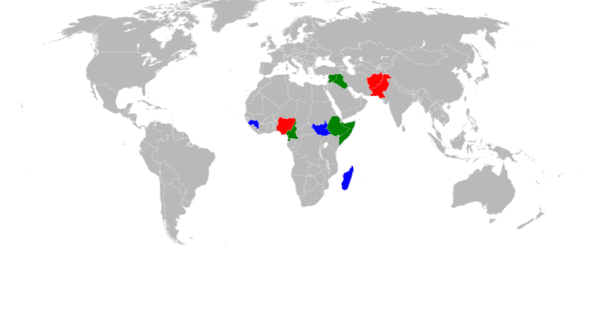

According to the World Health Organization “polio cases have decreased by over 99% since 1988, from an estimated more than 350 000 cases to 22 reported cases in 2017. This reduction is the result of the global effort to eradicate the disease. Today, just three countries in the world have never stopped transmission of polio (Pakistan, Afghanistan and Nigeria).”

The polio epidemic story sounds eerily familiar to what we are experiencing today: closure of schools, dental offices, restaurants, bars, hair salons, the list goes on and on. Will this be our new normal each spring?

Will COVID-19 rear its ugly head each year until a successful vaccine can be developed?

To get the answer to that question, we have to understand that polio was never, in fact, eradicated. That’s right, as the WHO noted, new cases popped up in Africa last year. And then in the Phillipines, for the first time in decades. The key is to achieve herd immunity, an eradication rate of at least 95 per cent that slows the disease down to less than a crawl.

According to the CDC, an influenza vaccine takes at least six months to mass produce. But most vaccine development can often take ten to fifteen years.

In the United States, public health officials say it could take eighteen months to produce a coronavirus vaccine. But what about that nasty issue of a recurrence of COVID-19? The Spanish Flu, to take an elephant in the room example, came in three waves, ultimately killing 50-million people.

To answer this we need to go back a ways. The first vaccine ever developed was by British doctor Edward Jenner, who in 1797 infected a patient with the mild cowpox to inoculate him against the smallpox virus. The word virus, in fact, derives from the Latin word for cow.

Flash forward to the nineteen fifties, when the World Health Organization implemented a global vaccination campaign that all but eradicated smallpox two decades later.

That’s right, smallpox, which had an effective vaccine in 1798, stuck around nearly two centuries later when it was eradicated. Note that we use the term “eradicated”, not “eliminated”. The two are sometimes used interchangeably but they are not the same.

Eradication is the permanent and complete reduction to zero of new cases of an infectious disease, worldwide. Elimination means the disease itself no longer exists.

So why don’t we worry about polio or smallpox or the Spanish Flu today when we go to the grocery store or to a public pool? It’s because they have been eradicated.

This makes the question of whether or not coronoavirus will be around in fifty years somewhat less mysterious. We do not yet have a vaccine, but we soon will. After that it’s a matter of administering it. And then the 95 per cent herd immunity number becomes important, as it was when the Spanish Flu was ripping through the crowded trenches in World War One Europe.

In eighteen, maybe twelve, hopefully six months we will possess a vaccine for COVID-19. At that point, the only question we can ask as a society is “Do we want coronavirus around for fifty years?”

Tara Whittet

Writer

Tara Whittet is Senior Sales Manager at Cantech Letter.