What would famous economists say about the Tim Hortons minimum wage debate?

“Hold the sugar, hold the cream. Come on Tim Hortons, don’t be so mean.”

In dozens of towns and cities across Canada this week, thousands of people gathered to protest the actions of one of Canada’s most iconic businesses. After the Ontario government on January 1 implemented a new minimum wage of $14.00, hiking it from $11.60, some Tim Hortons franchisees decided to cut back on certain employee benefits because they have no power to raise prices in response to the law.

What ensued was a one-day boycott and a fresh debate over minimum wage laws. A popular meme making the rounds today was culled from the CBC show The Mercer Report.

“If you ever wondered why we need minimum wage labour standards in this country, look no further,” host Rick Mercer said on the the January 17 episode of the CBC show. “Leave it up to some of these owners, every Hortons in the country would be staffed by grandmothers doing 12 hours shifts for tea bags.”

The battle lines are drawn as clearly as the blue line Tim Horton himself patrolled for 21 years with the Maple Leafs. The fight for minumum wage laws has populist appeal. But will it produce a better result for Canada?

I think almost all economists think that the minimum wage has two main effects. One is to boost pay for low-wage workers and the second is that there would be some amount of negative impact on employment…

The concept of a minimum wage is not a new one. It can be traced all the way back to the beginnings of English labour law in 1349 when King Edward III first bandied about the concept of a “living wage”. Of course, Eddy was a little more concerned about a maximum wage than a minimum one, a preoccupation that was made moot when the Black Death killed about 40 per cent of his labour pool, a development that kinda sorta forced his hand on the matter.

But given normal circumstances, what is the right move for a society? It’s a question most every economist has had to answer at some point.

Former U.S. Federal Reserve Chief Janet Yellen’s position was typical of the push and pull many economists have had on the matter.

“I think almost all economists think that the minimum wage has two main effects,” Yellen said about then president Barack Obama’s bid to raise the U.S. minimum wage to $10.10 an hour. “One is to boost pay for low-wage workers and the second is that “there would be some amount of negative impact on employment.”

Most economists, myself included, assumed that raising the minimum wage would have a clear negative effect on employment. But they found, if anything, a positive effect…

But the New York Times’s resident economist Paul Krugman says wait a second, that’s not necessarily true.

“More than two decades ago the economists David Card and Alan Krueger realized that when an individual state raises its minimum wage rate, it in effect performs an experiment on the labor market,” Krugman said in a 2015 editorial. “Better still, it’s an experiment that offers a natural control group: neighboring states that don’t raise their minimum wages. Mr. Card and Mr. Krueger applied their insight by looking at what happened to the fast-food sector — which is where the effects of the minimum wage should be most pronounced — after New Jersey hiked its minimum wage but Pennsylvania did not. Until the Card-Krueger study, most economists, myself included, assumed that raising the minimum wage would have a clear negative effect on employment. But they found, if anything, a positive effect. Their result has since been confirmed using data from many episodes. There’s just no evidence that raising the minimum wage costs jobs, at least when the starting point is as low as it is in modern America.”

Then there’s James Galbraith, the son of the most famous Canadian-born economist, John Kenneth Galbraith, who takes Krugman a step further, arguing that governments need to be even more aggressive about raising the minimum wage.

“What would workers do with the raise? They’d spend it, creating jobs for other workers,” Galbraith says. “They’d pay down their mortgages and car loans, getting themselves out of debt. They’d pay more taxes — on sales and property, mostly — thereby relieving the fiscal crises of states and localities. More teachers, police, and firefighters would keep their jobs.”

These people confuse wage rates with wage income. It has always been a mystery to me to understand why a youngster is better off unemployed at $1.60 an hour than employed at $1.25…

Galbraith here was talking here in 2012 about a minimum wage he thought should be raised to more than $12.00 an hour to its then current $7.25.

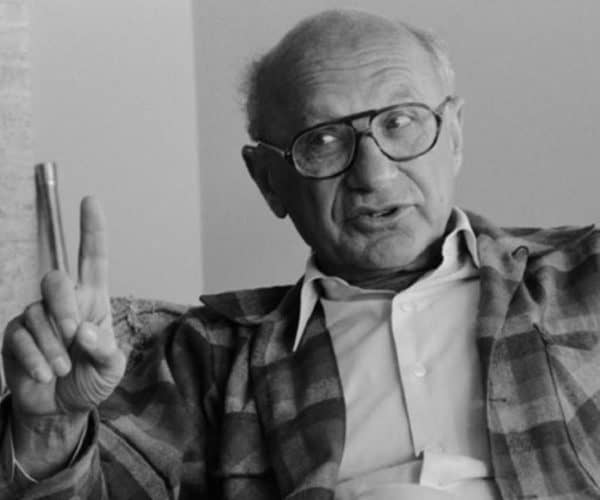

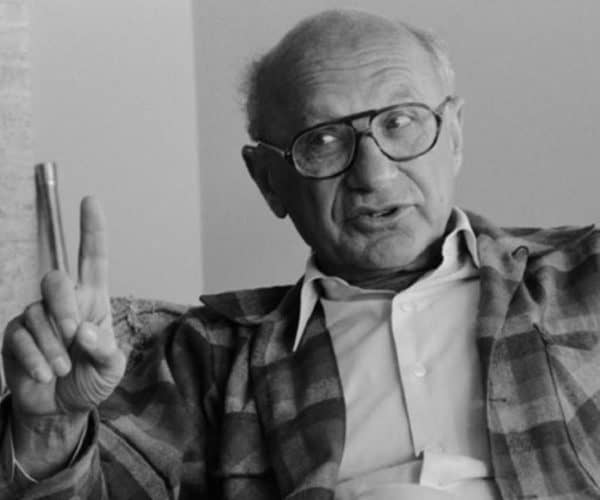

But back when the minimum wage was raised from $1.25 to $1.60, in 1968, there were dissident voices. Small government proponent Milton Friedman argued that the American public was being swindled.

“Many well-meaning people favor legal minimum-wage rates in the mistaken belief that they help the poor,” Friedman said in an op-ed for Newsweek. “These people confuse wage rates with wage income. It has always been a mystery to me to understand why a youngster is better off unemployed at $1.60 an hour than employed at $1.25. The rise in the legal minimum-wage rate is a monument to the power of superficial thinking.”

And what of the man who helped steer the U.S. out of the financial crisis of 2008 with a healthy dose of corporate welfare? Surprisingly, Ben Bernanke thought the minimum wage was kind of a non-issue. Bernanke argued that minimum wage laws affected less than two per cent of Americans.

Bernanke, if he were to weigh in on the Tim Hortons debate, would likely argue for training to get existing workers off the minimum wage carousel.

“The research on this is controversial,” he said. “Some people argue that the effect is very small. Others think it’s larger. My inclination is to say that you’d like to find ways of increasing the return to work which don’t have the effect of potentially shutting some people out of the workforce. And so I think I would agree that — and I’ve said this in previous testimony — that the earned income tax credit, which provides extra income to people who are working, and skills and training, increased training for increased skills and productivity, are in my opinion probably more effective ways to approach this question.”

But Bernanke made this argument more than a decade ago. Michael Farren, a research fellow with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, argued in the Globe and Mail just last week what many now see as an inevitability. The likely outcome of the whole debate is increasing levels of automation.

There’s no minimum wage for robots, as fast food chain Wendy’s recently took full advantage of.

Nick Waddell

Founder of Cantech Letter

Cantech Letter founder and editor Nick Waddell has lived in five Canadian provinces and is proud of his country's often overlooked contributions to the world of science and technology. Waddell takes a regular shift on the Canadian media circuit, making appearances on CTV, CBC and BNN, and contributing to publications such as Canadian Business and Business Insider.