Fast is generally good. Fast food. Fast wait times. Fast friends. A fast Arctic glacier is decidedly a bad thing.

Fast is generally good. Fast food. Fast wait times. Fast friends. A fast Arctic glacier is decidedly a bad thing.

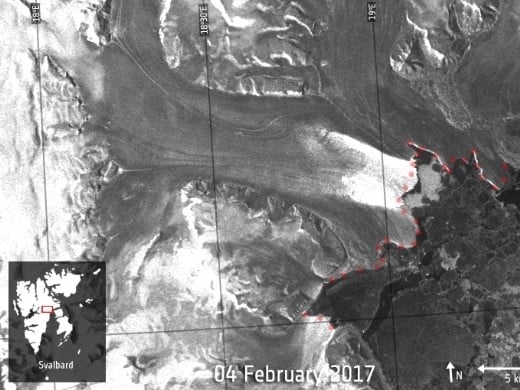

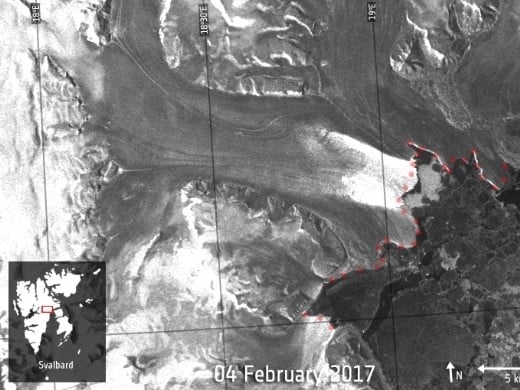

A European Space Agency satellite has been tracking the flow of a glacier in Norway’s Svalbard archipelago, one that has lately been on the move in a big way.

Researchers mapping glaciers in the high Arctic used data from the Sentinel-1 satellite to track the movement of the Negribreen glacier on Spitsbergen island and have found that it increased its daily growth rate during the past year from an average of one metre a day to a surprising 13 metres, a speed which hasn’t been observed since the 1930s.

The Negribreen glacier stretches 1,180 square kilometres across the western part of Spitsbergen Island in Svalbard and at 40 kilometres along the coast has the widest calving front of Spitsbergen’s glaciers. Named after the Italian geographer Christoforo Negri, Negribreen has been on a steady retreat since its last surge between 1935 and 1936 when it advanced a full 12 kilometres in one year.

The ESA’s Sentinel-1 mission actually involves two radar satellites which provide continuous radar mapping of the Earth, monitoring sea ice zones, mapping land surfaces and even adding support during crisis situations such as the 2014 South Napa earthquake in San Francisco where Sentinel-1A was used to map out the areas affected by the quake.

“Sentinel-1 provides us with a near-realtime overview of glacier flow across the Arctic, remarkably augmenting our capacity to capture the evolution of glacier surges,” said Tazio Strozzi from Swiss company Gamma Remote Sensing. “This new information can be used to refine numerical models of glacier surging to help predict the temporal evolution of the contribution of Arctic glaciers to sea-level rise.”

Glacial movement is caused by gravitational pressure from the build-up of snow and ice, which gradually deforms the lower layers due to the added weight. Glaciers can be in advance or retreat depending on whether snow is building up or evaporating, but the more rare activity of glacial surge occurs when a mass of ice flows to the end of the glacier’s front, sometimes occurring over a period of weeks or months at a time.

The Tweedsmuir Glacier in northern BC recorded a surge in 2008 which took it across 300 metres in just ten months and raised concerns of it damming up the Alsek river. In 1986, the Hubbard Glacier in Alaska surged at a rate of ten metres a day across the mouth of Russell Fjord and succeeded in damming up the fjord, creating a lake behind it.

Glaciers are sensitive to temperature fluctuations and are currently in retreat the world over, thanks to climate change. Research has found that ice melt from Canada’s Arctic glaciers, which hold 25 per cent of all Arctic ice, is already becoming a significant factor contributing to the rise in sea levels.

Earlier this year, scientists from the University of California Irvine concluded that the way glaciers are losing their mass has changed over the past decade. Whereas before 2005, 52 per cent of ice loss came from iceberg calving from glaciers into the ocean and 48 per cent from ice melting on the surface of glaciers, since 2005, surface ice melt has been contributing 90 per cent of total ice loss.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Share

Share

Comment