Scientists are close to cloning a woolly mammoth

The dream of bringing back to life a long-extinct species such as the woolly mammoth is close to becoming a reality, as scientists at Harvard University say that they are just two years away from creating a hybrid embryo with DNA traits of a woolly mammoth, a species that was last seen on Earth 4,000 years ago.

The science of genetic engineering has been progressing in leaps and bounds over the past few years, mostly thanks to the gene editing tool known as CRISPR-Cas9, which allows researchers to essentially hand-pick specific genetic markers that they wish to either add or subtract from a given line of DNA. The tool holds a wealth of promise in the treatment and prevention of disease and in crop production, but it also leaves the door wide open for manipulating genetic traits so as to create new — or in this case, very old — creatures.

“Our aim is to produce a hybrid elephant-mammoth embryo,” said Professor George Church, geneticist at Harvard Medical School and Professor of Health Sciences and Technology at Harvard and MIT, to the Guardian. “Actually, it would be more like an elephant with a number of mammoth traits. We’re not there yet, but it could happen in a couple of years.”

The Jurassic Park version of resurrecting ancient beasts is well known: you find a sample of an extinct animal’s DNA (the old “mosquito preserved in a lump of amber” trick) and inject it into egg cells that have had their own DNA removed and, twelve or however many months later, voila! T-Rex is alive and kicking!

In fact, research has shown that strands of DNA break down very quickly, regardless of method of preservation, so this approach is more than likely a dead end. But the process can also be approached constructively, by taking another creature’s DNA, like the elephant, and making genetic adjustments — a bit of a thicker coat here, some smaller ears there — in order to cobble together something not exactly identical to the woolly mammoths of old but close: a “mammophant,” to be precise.

Professor Church says that since 2015, he and his team have made 45 splices of mammoth DNA edits into the elephant genome but still have a ways to go. “We already know about ones to do with small ears, subcutaneous fat, hair and blood, but there are others that seem to be positively selected,” Church says.

Once the editing has been completed, the team plans to grow the hybrid mammophant in an artificial womb, something that they’ve already done with mouse embryos. “We’re testing the growth of mice ex-vivo. There are experiments in the literature from the 1980s but there hasn’t been much interest for a while,” says Church. “Today we’ve got a whole new set of technology and we’re taking a fresh look at it.”

Yet, having the technology and using it in ethically appropriate ways are two separate things, of course, with some arguing that the whole idea of de-extincting a creature like the wooly mammoth is ethically suspect. Tori Herridge, paleobiologist with the Natural History Museum in London, is one who says that the resurrection project should not go ahead, arguing that the attempt has very little merit in terms of advancing scientific knowledge for the betterment of life on Earth.

There are claims being made, for instance, that putting wooly mammoths back onto the Arctic tundra might stabilize the ecosystem and help slow down climate change. But in fact, we have no proof at all that such a plan would work, says Herridge. Neither does she see any value to the argument that we’re advancing the science of gene editing by applying it to the wooly mammoth, as there are tonnes of other more directly useful projects in gene editing to be undertaken which do have obvious scientific merit.

In the end, Herridge says, mammoth resurrection is an interesting concept but nothing more. “Why should we clone a mammoth?” says Herridge. “Because it would be cool to see one? That’s not going to cut it, I’m afraid. If the reason is that it’s easier to get funding for cloning a mammoth, then all of us need to take a good long look at our priorities.”

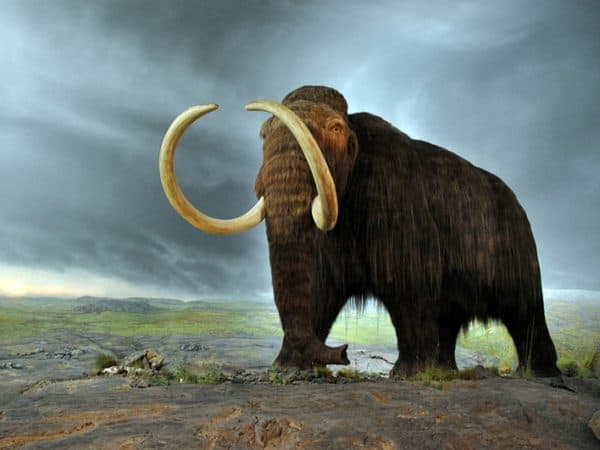

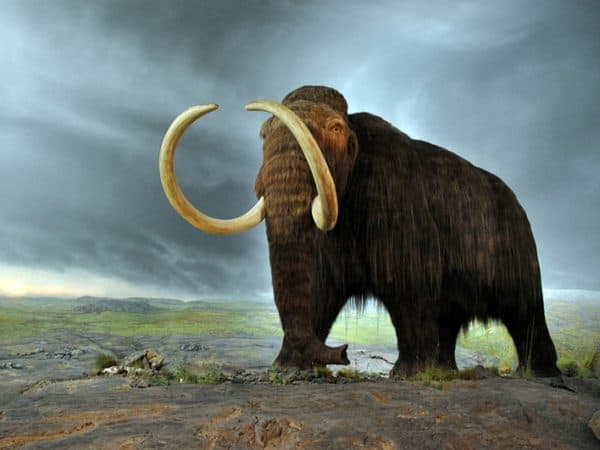

The woolly mammoth lived during the Pleistocene epoch in northern Europe, Asia and North America, from about 400,000 years ago up until its extinction, which began about 40,000 years ago. The last known population of wooly mammoths lived until about 4,000 years ago on Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean. Wooly mammoth remains, including some full skeletons, have been found around the world preserved in ice and permafrost. As recently as 2015, a woolly mammoth tusk was found a few kilometres outside of Saskatoon by a gravel company, later identified by researchers at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum.