Toronto 3D scanning and printing company Matter and Form Inc. is one of three companies that have filed an amicus brief in support of Star Athletica, a Missouri-based manufacturer of cheerleader uniforms, as part of their case currently before the United States Supreme Court against Varsity Brands, the world’s largest manufacturer of cheerleading and dance team uniforms, which may have an impact on the future of intellectual property concerns surrounding 3D printing.

Toronto 3D scanning and printing company Matter and Form Inc. is one of three companies that have filed an amicus brief in support of Star Athletica, a Missouri-based manufacturer of cheerleader uniforms, as part of their case currently before the United States Supreme Court against Varsity Brands, the world’s largest manufacturer of cheerleading and dance team uniforms, which may have an impact on the future of intellectual property concerns surrounding 3D printing.

What does an intellectual property dispute between two cheerleader uniform manufacturers have to do with your eventual right to 3D print an object in your home without fear of being sued for copyright infringement, you might reasonably ask?

As the trio of 3D printing companies makes clear in their amicus brief, the case hinges on how the Supreme Court settles the matter of “conceptual separability doctrine”, which previous courts, including the US Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit, had reached split decisions on, with Star Athletica winning the first round in district court, only to see that decision overturned by a later panel who sided with Varsity Brands.

As Paul Banwatt, COO and general counsel for Matter and Form Inc., told IP Fridays last year, “Anytime you invent a new copying machine, whether it’s the printing press or a computer, or a photocopier, I think you create a set of IP issues that are interesting to IP practitioners and their clients so that’s why I think this is such a hot topic. We’ve essentially created new copying machines here.”

“The present case presents a critical opportunity to resolve this uncertainty and remove the chill it creates on innovation,” writes the trio of 3D printing companies supporting the petition. “In the $330 billion apparel industry, this Court’s setting of ‘the standard analytical tests all courts use to determine copyrightability’ would ‘lead to greater predictability when it comes to determining parties’ rights and liabilities.'”

The other two companies filing the amicus brief with Matter and Form are Massachusetts-based Formlabs and New York-based, Dutch-founded Shapeways, who are looking to the Supreme Court to clarify “which aspects of their work are protected and which aspects may be reused in new creative works.”

Are we seriously discussing copyright infringement over the design of a cheerleader costume?

Yes, and where the Supreme Court comes down on this will have a significant impact on one company’s ability to litigate for what they regard as their intellectual property, even when that design seems unenforceable.

Remember Apple’s “victory” against Samsung in 2012 claiming copyright protection on its iPhone’s rounded corners? That case is also headed to the Supreme Court later this year, since it was successfully appealed by Samsung last year in district court.

But the cheerleader costume design infringement case will likely precede Apple v. Samsung, and so provide a clearer definition on the legal parameters around manufacturing utilitarian objects, such as mobile phones or cheerleading outfits.

And this is where the 3D printing companies take an interest.

The 3D printing industry is paying close attention to how a case involving intellectual property claims for the design of rival cheerleader uniforms turns out. And so should we all.

Legal proceedings on this case began in 2010, when Star Athletica published a catalog of cheerleading uniforms, which attracted a lawsuit from Varsity Brands, alleging that Star had violated copyright on Varsity’s designs.

As Star Athletica makes clear in its petition to the Supreme Court, if the previous circuit court decision is not overturned, then industrial designers will be able to claim copyright protection “for pleats on tennis skirts, button patterns on golf shirts, and colored patches on rugby uniforms,” which sounds a lot like Steve Jobs and Apple trying to take credit for rounded corners on a phone.

“As the capacity to 3D scan and 3D print becomes increasingly available to everyday consumers, a clear copyright test is the only way to ensure that companies and customers can safely unlock the full value of this new technology,” reads Matter and Form’s “Interest of Amici Curiae” statement.

“The application of copyright law to 3D printing is sometimes clear,” reads the Argument section of the amicus brief. “3D printed objects that are purely ornamental and nonfunctional, such as an exact replica of a sculpture or a complex jewelry design, are protectable by copyright; designs that are purely functional useful articles, such as a basic wrench or a replacement gear, are not.”

So basically, if an object is purely utilitarian, like a wrench or a gear, its design is not copyrightable, but if there’s any art in the design at all, then there’s got to be some copyright wriggle room.

But what aspect of our built world is not designed, or touched somehow by art? Not one is the answer to that question. Someone can always claim to have designed any particular built object, whether it’s “functional” or not.

And when it comes to clothing, the law is especially murky.

What does an intellectual property dispute between two cheerleader uniform manufacturers have to do with your eventual right to 3D print an object in your home without fear of being sued for copyright infringement, you might reasonably ask?

Fashion design law is governed by something called the Idea/Expression Dichotomy, which asserts that the unique expression of an idea is protectable under copyright law, but not the idea itself.

So while the “unique expressions of an idea” makes it clear enough that I should not legally be allowed to distribute a 3D design of the Death Star from Star Wars or a My Little Pony doll that anyone with a 3D printer can then reproduce without getting chased by LucasFilm or Hasbro, it’s only because those are unique cultural properties that have a different purpose than a wrench or gear.

But what if I wanted to make a cheerleader costume? (Asking for a friend.)

What aspect of a cheerleader costume is a “unique expression”? The whole point of them is that they’re a uniform worn by practically identical cheerleading squads the world over.

The Star v. Varsity case demands that the Supreme Court settle “the fragmented state of the law surrounding conceptual separability”, so that the line between function and design is made to respect the intent of the 1976 Copyright Act, which sought to draw a distinct line between “copyrightable works of applied art and uncopyrightable works of industrial design.”

The 3D printing industry is paying close attention to how a case involving intellectual property claims for the design of rival cheerleader uniforms turns out. And so should we all.

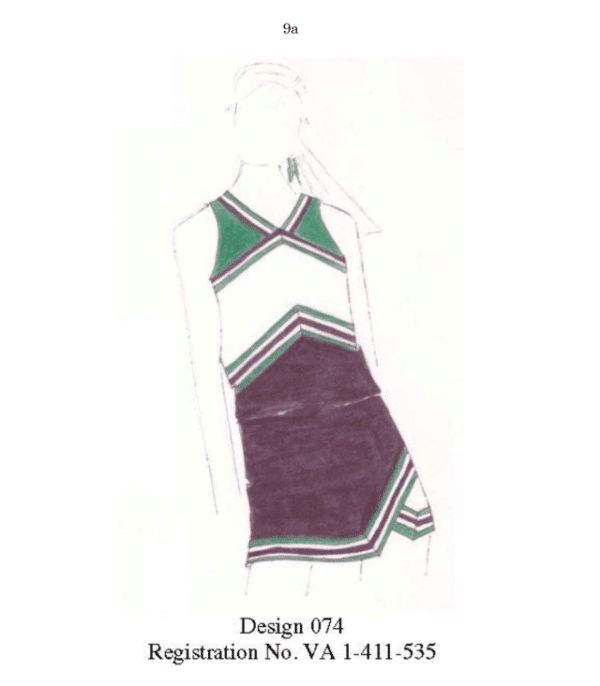

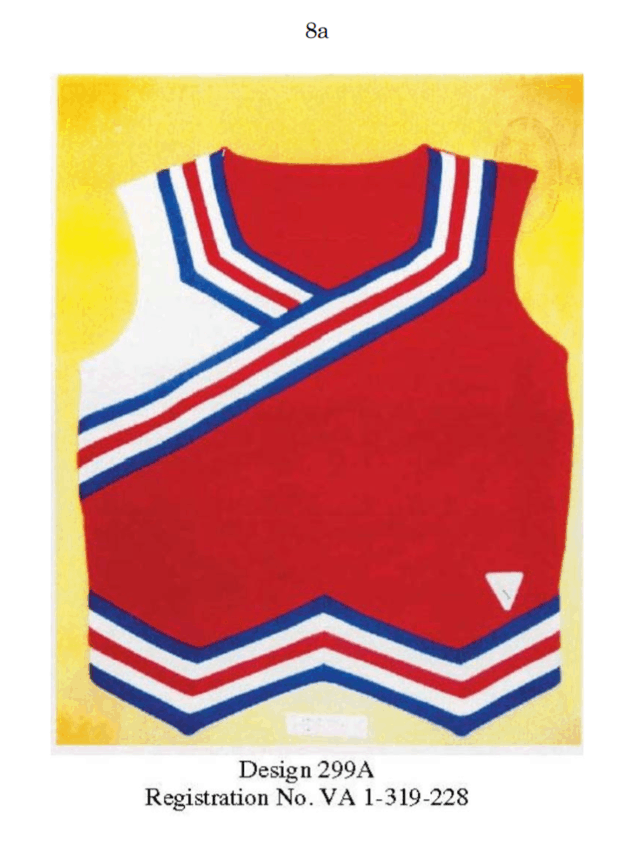

See below two examples of “two dimensional artwork” for which Varsity sought and received copyright protection under a previous circuit court decision.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Share

Share

Comment