Counterfeit Clothing is a billion dollar business

Counterfeit clothing and accessories are some of the largest counterfeit goods verticals. Luxury brands convey social status, a level of success that most people won’t achieve. And in order to show affluence, some of these people purchase counterfeit clothing and accessories sporting fake luxury logos. These consumers may not know nor care that the counterfeit goods trade incurs horrible social costs including exploitation of migrant and child labourers, job loss, and reduced tax revenue. Until the purchase of counterfeit goods becomes socially unacceptable, the trade will flourish. In the meantime, we introduce a technology that can publicly distinguish between fake and genuine labels and clothing, essentially diminishing the perceived affluence coming from “luxury” counterfeit goods.

Reasons to Read this Report

- Uncover the magnitude of the counterfeit clothing industry;

- Learn about the victims of the counterfeit clothing trade, and;

- We present a public company whose nanotechnology-based anti-counterfeiting technology can distinguish between genuine and counterfeit articles.

Introduction

Many counterfeit clothes look almost as good as the originals but cost only a fraction as much. Others – not (see side picture). Although consumers may enjoy the savings from these knockoffs, they probably don’t understand the social and economic costs resulting from their desires to get “good” deals. Counterfeits deprive governments of duties and taxes; they diminish corporate profits. But what many people don’t realize is that the sale of fake items has been linked to criminal and terrorist organizations; groups that disregard labour and environmental laws.

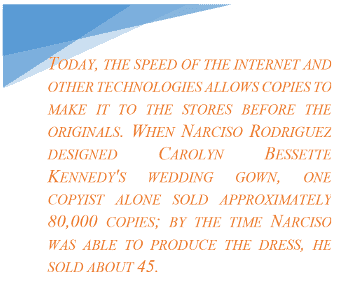

Corporations are fighting to protect their intellectual property and brands. And although authorities are constantly arresting counterfeiting criminals, the Internet has proven itself to be a sales channel that is difficult (but not impossible) to police. Yet, a larger problem fuels the counterfeit trade – social acceptance. The desire to look affluent, the thrill of buying a “brand” name at a discount, and the ease of online purchases has made counterfeit clothes and accessories palatable. People covet looking successful, and luxury clothing and accessories generate the ego-boosting public affirmation that many crave. A massive educational campaign is needed to curb the public’s appetite for fake fashion items. Or, brands need technology that renders the ego-boosting craving inert.

In this report, we introduce a company with a nanotechnology that we believe can differentiate between genuine and fake brands. This technology is visible and easily recognizable, shattering the illusion between genuine luxury and fraud. We believe that these nanotechnology-based anti-counterfeiting security features can not only decrease the demand for counterfeit clothing and accessories but also increase brand recognition.

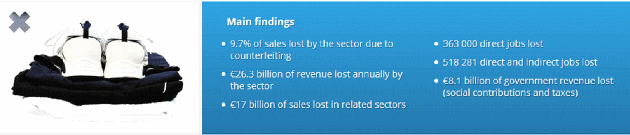

Counterfeit Clothing Market Size

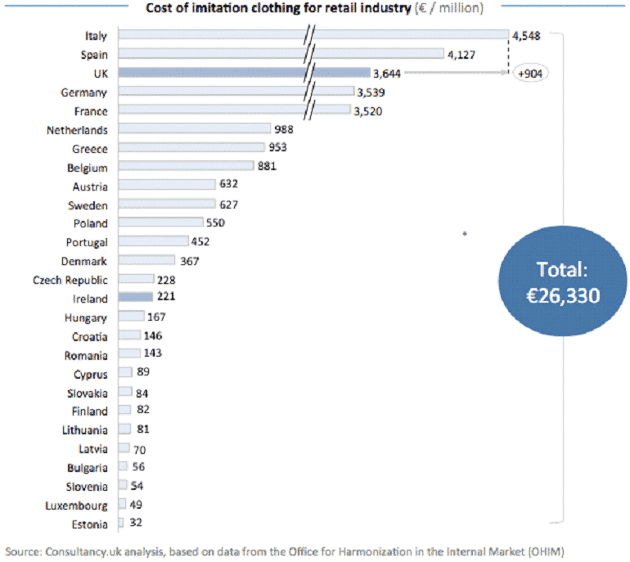

Counterfeit clothing cost the European Union over €26 billion (Exhibits 1 and 2). Adding the revenues lost from knock-on industries and government tax collection, this estimate swells to €43.3 billion. Exhibit 3 illustrates the magnitude of individual seizures globally including one worth almost half a billion dollars! This shows that counterfeit clothing is big business to the degree that it affects economies. The global anti-counterfeit clothing and accessories packaging market accounted for $12 billion in revenue in 2014 and is expected to reach $20.5 billion by 2020, registering a CAGR of 9.9% over the forecast period, according to market research firm Allied Market Research.

Professor at Fordham University

Why the Counterfeit Clothing and Accessories Market Exists

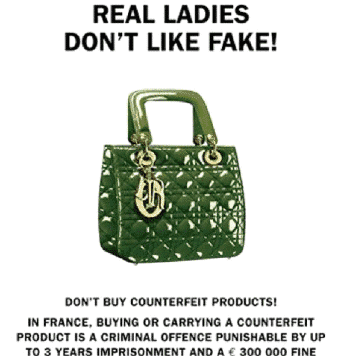

According to Psychology Today, people purchase luxury goods to convey a sense of status, wealth, and exclusivity. This perhaps explains why fake handbags are especially popular – the logos are visible to the public (unlike items such as socks and underwear). In other words, visibility feeds our egos.

Three-quarters of women admitted that they had knowingly purchased a counterfeit designer fashion item. Many of the 2,105 women surveyed said they had as many as five fake dresses, knockoff bags, wallets, jewelry or pairs of shoes.

Buying Counterfeit Goods is not Victimless

The general public are victims. According to INTERPOL, criminal organizations and terrorist groups are benefactors of the counterfeit fashion industry. The United Nations singled out the Camorra, the Mafia, and Yakuza triads as benefactors of the broader counterfeit trade. These groups disobey laws, bribe government officials, don’t pay taxes, and often force children and illegal immigrants to manufacture and sell the fakes. There are no safety or quality controls and these put consumers at risk. As a result, the general population is forced to make up shortfalls in government expenditures and pay for the health, environmental, and policing efforts that precipitate from the illegal goods trade.

INTERPOL dismantled a South American counterfeit ring and clearly established the link between counterfeit items and organized crime. Operation Jupiter VII saw 2,000 raids in 11 countries and led to the seizure of 800,000 fake goods worth $135 million, and 805 arrests. Operation Jupiter VI in 2014 netted $27.4 million of counterfeit goods across 10 countries. A Guangzhou, China-based gang pushed drug proceeds into Chinese casinos, factories, exchange houses, and export companies. This money was deposited into bank accounts and used to purchase counterfeit goods that were exported overseas. The counterfeit goods were sold and the money changed from local currency into American dollars.

Terrorist targets are victims. Sales of counterfeit goods by Charlie Hebdo attacker Cherif Kouachi helped fund the purchase of weapons. And we know what those guns were used for. If you think that the Charlie Hebdo attack was an isolated example of counterfeit goods funding terrorists, then think again:

Former INTERPOL Secretary General Ronald K. Noble connected the seizure of €1 million of counterfeit brake pads and shock absorbers in Lebanon to terrorists. “Subsequent enquiries revealed that profits from these consignments, had they not been intercepted, were destined for supporters of Hizbullah,” said Mr. Noble. “Linking the Hizbullah to counterfeit brake parts shows not only the link between terrorist financing and intellectual property crime, but also how intellectual property crime is not a victimless one – the potential danger to the public from this sort of criminal activity is too serious for governments and law enforcement to ignore.” Although fake auto-parts fall outside the scope of the counterfeit fashion trade, this example links how the terrorists fund their activities via the sale of counterfeit goods.

Workers in the clothing trade are victims. Counterfeit clothes, shoes, and designer handbags have caused the loss of about 518,000 direct and indirect jobs in Europe.

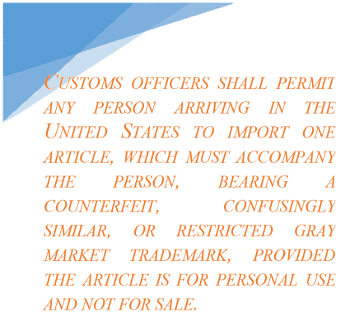

American taxpayers are victims via a customs directive. Surprisingly, Americans can legally import counterfeit goods. According to U.S. Customs Directive 2310-011A: “Customs officers shall permit any person arriving in the United States to import one article, which must accompany the person, bearing a counterfeit, confusingly similar, or restricted gray market trademark, provided the article is for personal use and not for sale.”

This directive affects the duties on imported clothes. In 2014, the U.S. government collected $13.5 billion in tariffs collected on imported shoes and clothes – about 42% of all duties collected. However, counterfeits entering the United States translates into fewer legitimate imports. These legally imported counterfeits decrease the flow of duties and sales taxes to Treasuries.

Legitimate businesses are victims. Counterfeiters are undercutting legitimate businesses. As real brands improve their labour and workplace manufacturing standards internationally, criminal organizations have moved operations into sweatshops to take advantage of the low costs and non-existent labour laws.

Animals are victims. Many celebrities are sporting designer handbags made from exotic leathers. As a result, legal imports of these skins have grown from 350,000 skins worth €100 million in 2005 to $1 billion in 2014. Unfortunately, because of this fashion trend, the illegal market for skins has ballooned to possibly the same size as the legal market. Unfortunately, dogs are making their way into the trade with a hood lined with German Shepard fur.

Worse, illegal immigrants are victims. Criminal organizations exploit illegal immigrants to sell counterfeit goods. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, illegal immigrants are the most common conduit for the distribution of counterfeit goods. As such, these people bear the brunt of policing efforts even though they are a symptom of the counterfeiting industry and not the cause. One Senegalese immigrant selling counterfeit Nike-branded FC Barcelona shirts in Barcelona lamented police harassment and the unpredictability earnings of his trade: In winter months, he lamented that he makes about €150 a month.

Source: The Star

Worst of all, children are victims. Criminal organizations exploit child labour in the production of counterfeit goods. Valerie Salembier, the President of Authentics Foundation, noted that the counterfeit industry, “…supports child labor, 7-year-olds chained to sewing machines, eating two meals of rice a day.” Ms. Salembier was the Harper’s Bazaar publisher when the magazine printed a story about the counterfeit goods industry in January 2009. The article included a view from inside a factory in Guangzhou, China, where two dozen children aged 8 to 14 were sewing counterfeit designer bags.

Dana Thomas, author of Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster, wrote about a similar experience: “I remember walking into an assembly plant in Thailand a couple of years ago and seeing six or seven little children, all under 10 years old, sitting on the floor assembling counterfeit leather handbags,’ an investigator told me… ‘The owners had broken the children’s legs and tied the lower leg to the thigh so the bones wouldn’t mend. [They] did it because the children said they wanted to go outside and play.’” Child labor laws are not at the forefront of criminal minds.

Source: ITV

There’s still one thing related to the counterfeit clothing trade that we cannot quantify. In a 2013 report, the International Chamber of Commerce believed that global counterfeiting and piracy could be a $1.7 trillion industry by 2015. With this type of money at stake and little chance of getting caught, criminal organizations have embraced the high-margin, counterfeiting industry. To improve margins, costs are cut – not only by employing labour at slave wages (if workers get paid at all) but also by using unsafe raw materials. Given this, we don’t know what the global health consequences and mortality rate is due to the counterfeit clothing industry.

Clothes

Source: Racked.com

Counterfeiters like to tap into major sporting events such as the Stanley Cup playoffs. During the 2013 Stanley Cup playoffs, police and the NHL impounded close to 11,000 counterfeit articles worth $2.5 million. In fact, 10.6 million pieces of fake merchandise worth $405.5 million were seized since 1992.

The NFL’s Carolina Panthers cracked down on counterfeiters last December. Police confiscated over 800 items worth US$21,000 that violated Panthers trademarks. Counterfeit Panthers gear was also found on a Chinese website mimicking the authentic online NFL shop. The counterfeits were easily recognizable because the Panthers gear was the wrong colour. The website, www.nfl-us.com is still active, and their FAQ notes that if the product ships with a stain, “…we hope you can wash it or clean it…” before applying for a refund.

Designer Handbags

Designer Handbags

Those gorgeous designer handbags are out of reach for most women. The prices are too high. Hermes’ Birkin bag retails at over $60,000; a Fendi baguette costs about $3,000; a 2.55 Chanel bag comes with a $4,000 sticker; a mid-size Lady Dior handbag could cost $7,200. In the unicorn department, limited-edition designer bags can be a $100,000 investment; one lucky lady received a diamond-studded Ginza Tanaka handbag worth $1.9 million.

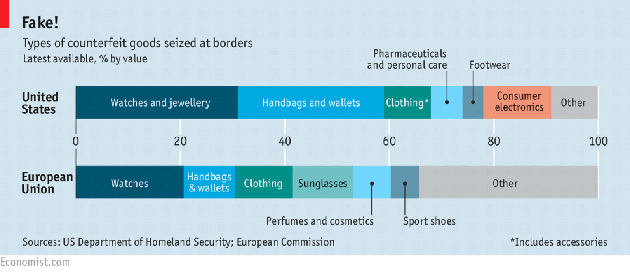

Because of the astronomical prices for luxury purses, handbags are the most popular counterfeit goods sold in the United States (Exhibit 4). For women, bags are usually the most attainable and recognizable accessory. Logo visibility feeds egos causing us to seek out social status through branded looks.

Bargain handbag purchases tend to ramp around Christmas time and Mothers’ Day, as well-intending people search for ways to give designer bags as gifts without breaking the bank account. Coincidentally, these holidays coincide with increased designer handbag thefts. So even if you’ve done all your research and can tell a fake designer handbag from a genuine one, if its price is too good to be true then the handbag is probably stolen.

Back in August, 2015, U.S. Customs stopped the shipment of over $1 million of fake Gucci and Louis Vuitton bags through the Miami seaport. There were close to 2,300 counterfeit handbags hidden in 825 cartons. But this seizure pales in comparison to a raid in Manila, The Philippines that netted $22 million in falsely labeled bags. Exhibit 3 showed several other large seizures, and what these heists tell us is that there is a market for counterfeit bags – a BIG market.

A Los Angeles Counterfeit Handbag Showroom

While wandering though Los Angeles’ Santee Alley last December, we were approached by a young man asking if we were looking for designer handbags. Right away, we knew that the guy was selling fakes – no designer brands have stores in this discount section of L.A.’s Fashion District. Still, we were curious and followed the fellow through a side alley to a parking garage enclave. There, several men in their twenties converged with plastic bags and suitcases filled with Chanel, Louis Vuitton, and Coach handbags, to name a few. While we sifted through the fakes, nervous, burly fellows paced the alley, on the lookout for the police. Suddenly, one of the lookouts whistled; the vendors closed shop in less than 5 seconds and scrambled away. One waved us through a parking garage door and led us down four flights of dark stairs. At the bottom of the staircase, we entered an isolated utility room that served as the warehouse. Hundreds of fakes were on display, ranging in price from US$40 to US$160. We asked the young man why he sold the fakes: He shared that he had recently arrived from Mexico and had a newborn son to support. Without authorization to work in the United States, this was the only work he could muster. His peers shared similar stories.

Shoes

Shoes are another popular item to counterfeit. In our travels through developing nations, counterfeit shoes markets are as popular as the local plonk. And in some cases, the quality exceeds that of the original. One Italian textile manufacturer visited China to investigate the factories that had been counterfeiting his shoes, poorly for years. Upon his arrival, he was shocked that the quality matched his work and in some cases surpassed it.

Over 3 months in 2006, German customs officials made what could be the largest, single, counterfeit goods seizure of all time. A total of 117 shipping containers loaded with 945,384 pairs of fake Nike shoes, about 105,000 pairs of fake Adidas sneakers and Puma shoes, 76,760 knockoff watches, and 1,454 toys were confiscated. Officials estimated the value of equivalent quantities of the genuine brands at €383 million.

Enforcement

Worldwide, customs and borders officials seize less than one-tenth of one percent of all imports.

Although many law authorities around the world treat counterfeiting as a serious crime, some punishments meted by the courts almost seem indifferent (although The Philippines Bureau of Customs ran $1 million worth of fake sneakers through industrial wood chippers). Englishman Ian Guy ran an annual £250,000 global counterfeiting clothing operation that stole the Porsche and Yamaha brands as well the brand equity of a host of pop singers. He was issued several “warnings” to stop his online enterprise, yet continued. Finally, he was sentenced to six months and ordered to pay £130,000 in fines. Financially, crime can pay.

Released from jail after serving time for counterfeiting – operation restarts the same day. Nazakat Hussain, who was incarcerated for two years and ordered to pay £250,000 for dumping £1 million worth of counterfeit goods in London markets, recommenced his “business” the same day he was set free. However, Hussain and his partner were caught, and their warehouse held £490,000 of fake merchandise. This time, he was sentenced to three years in prison.

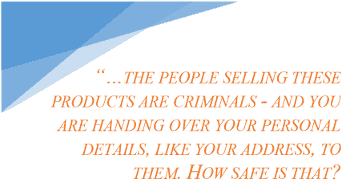

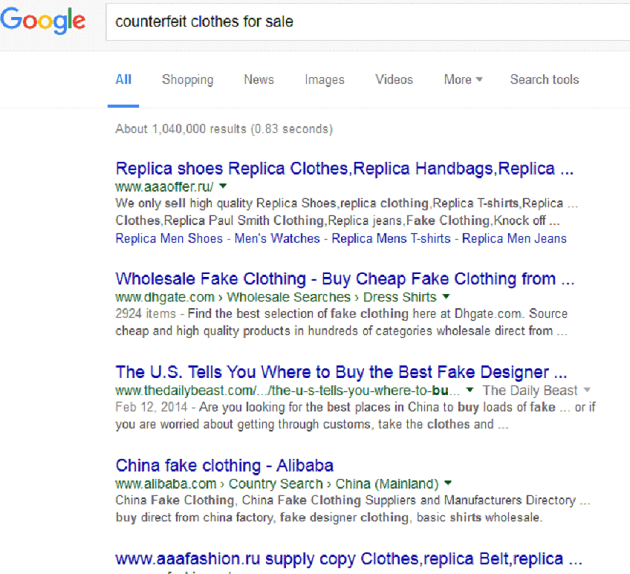

Arrests and prosecutions of criminals have barely dented the global counterfeit clothing industry. With the crackdown on brick-and-mortar counterfeit businesses, fake products peddlers have moved their clothing stores online, where it’s easy to elude authorities (the agility of the criminals outpaces the speed of the legislation). Fraudsters can set up their websites, remove them, and relaunch with ease while continuously evading authorities. Some estimates peg that one out of every six products sold online could be fake, and in the EU, 30% of confiscated counterfeit goods originated from Internet distribution channels. These numbers aren’t hard to believe if you conduct a simple Google search for fake clothes for sale (Exhibit 5). Counterfeit goods online seem as easy to get as smartphone apps.

Industry groups are targeting larger online retail websites to crackdown on counterfeit goods. On July 17, 2015, the American Apparel & Footwear Association, a group representing over 1,000 brands, issued a letter to Alibaba (NYSE:BABA) Chairman Jack Ma with a proposal to remove counterfeit goods sold through the platforms. This followed a May 2015 lawsuit launched by Kering SA (EPA:KER), which owns luxury brands including Gucci and Balenciaga, alleging that Alibaba encouraged and profited from the sales of counterfeit goods. Alibaba said the complaint had no basis.

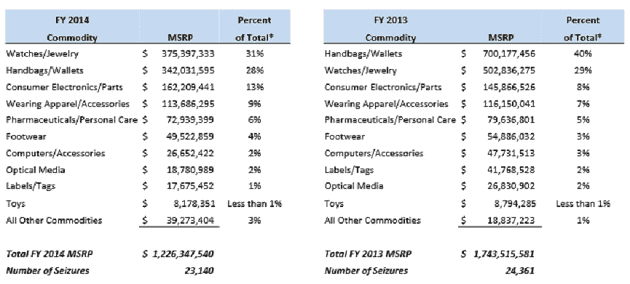

Exhibit 6 demonstrates that efforts by U.S. authorities cracking down on counterfeit clothing (and fakes, in general) are effective). The value of counterfeit goods seized decreased by 30% in 2014 compared to 2013. At first glance, this could suggest that policing was not as effective as in 2013. However, in 2014 the number of seizures decreased 5% year-over-year. This indicates that policing is relatively stable.

So what accounts for the annual 30% MSRP decrease in goods confiscated during 2014? The largest drops year-over-year from a MSRP perspective occurred in the watches/jewelry and handbag/wallet categories. Counterfeit handbag/wallet MSRP fell 31% annually, and the total number of seizures in the apparel and accessories categories decreased 20%. An annual 31% decrease in value in fake handbag/wallets from 20% less confiscations? To us, this suggests that counterfeiters are moving downstream in terms of luxury-branded fakes.

How Nanotechnology Can Stem the Rise of Counterfeit Fashion

Nanotech Security (NTS:TSXV; NTSFF:OTCQX), a Sophic Capital client, has the technology that fashion companies can use to differentiate genuine items from fakes. Nanotech Security’s technology is KolourOptik™, a nanoscience solution based upon the optical properties of the blue morpho butterfly. KolourOptik™ creates a grid of nano-sized holes that replicate the interaction light has with this butterfly’s wings. The result is the creation of vibrantly-coloured, butterfly effect images that appear similar to LEDs when illuminated adding not only a highly secure anti-counterfeiting feature but also brand recognition.

KolourOptik™ can be applied to a variety of surfaces including fabrics, pharmaceuticals, and banknotes – any type of packaging. There is no additional need for dyes or pigments. Imagine walking down the street with a genuine designer handbag or dress. A tiny, non-peel-able “hologram” above the handbag’s clasp or along the dress’s seam could change colours (note the plurality) as light reflects off the KolourOptik™ design. A hologram can be peeled off and likely would not endure many washings. KolourOptik™ designs become part of the fabric surface and will last beyond the clothing stores where consumers purchase the articles.

KolourOptik™ alone could reduce consumers’ willingness to purchase fake clothing, since the public would immediately know that the article is fake. This reduces many consumers’ social currency since the perception would be that he/she cannot afford the genuine article.

Source: Nanotech Security

KolourOptik™’s is nearly impossible to duplicate. Unlike holograms, which can be peeled off, KolourOptik™ images are embedded into the packaging, the product, or both. This technology is near impossible to counterfeit, given the complexity of the KolourOptik™ stamps (which are easily embedded in any manufacturing process). Plus, counterfeiters would need to invest in multimillion dollar equipment to produce the stamp and have advanced degrees in nanoscience and/or optics. As an extra level of authenticity, fashion houses could even embed data in the design thereby allowing all points in the supply chain to track and authenticate the article of clothing.

KolourOptik™’s eye-catching features engage end-users. Whether it’s on clothing, banknotes, liquor bottles, or directly embedded onto pharmaceutical pills, the key to a successful anti-counterfeiting technology is getting the end-user to engage. KolourOptik™’s LED like vibrancy pops and draws the user to interact with it. Thus, we believe pharmaceutical companies would only have to issue one campaign, detailing the differences between traditional holograms and KolourOptik™ technology. It wouldn’t matter what image or text is embedded on pills since KolourOptik™’s features are unique in anti-counterfeiting technology.

For more information about how KolourOptik™ can stem the counterfeit money and pharmaceutical industries, please refer to the following Sophic Capital research reports:

- Counterfeit Money: Keeping a Step Ahead of Criminals (January 7, 2015)

- Counterfeit Pharmaceuticals (April 8, 2015)

Conclusions

Criminals and terrorists are the biggest benefactors of the counterfeit clothing industry. Consumers who knowingly and unknowingly purchase fake clothes may think that they are getting a deal on real-looking brands; however, many don’t realize that child labourers, illegal immigrants, and the environment suffer. Until the public perceives the consumption of counterfeit clothing as abhorrent behaviour, (an unlikely outcome) we believe the counterfeit clothing industry will continue to flourish. However, we have identified Nanotech Security’s KolourOptik™ technology as a potential solution to retard counterfeit clothing consumption.

Disclaimers

The information and recommendations made available here through our emails, newsletters, website, press releases, collectively considered as (“Material”) by Sophic Capital Inc. (“Sophic” or “Company”) is for informational purposes only and shall not be used or construed as an offer to sell or be used as a solicitation of an offer to buy any services or securities. You hereby acknowledge that any reliance upon any Materials shall be at your sole risk. In particular, none of the information provided in our monthly newsletter and emails or any other Material should be viewed as an invite, and/or induce or encourage any person to make any kind of investment decision. The recommendations and information provided in our Material are not tailored to the needs of particular persons and may not be appropriate for you depending on your financial position or investment goals or needs. You should apply your own judgment in making any use of the information provided in the Company’s Material, especially as the basis for any investment decisions. Securities or other investments referred to in the Materials may not be suitable for you and you should not make any kind of investment decision in relation to them without first obtaining independent investment advice from a qualified and registered investment advisor. You further agree that neither Sophic, its employees, affiliates consultants, and/or clients will be liable for any losses or liabilities that may be occasioned as a result of the information provided in any of the Company’s Material. By accessing Sophic’s website and signing up to receive the Company’s monthly newsletter or any other Material, you accept and agree to be bound by and comply with the terms and conditions set out herein. If you do not accept and agree to the terms, you should not use the Company’s website or accept the terms and conditions associated to the newsletter signup. Sophic is not registered as an adviser under the securities legislation of any jurisdiction of Canada and provides Material on behalf of its clients pursuant to an exemption from the registration requirements that is available in respect of generic advice. In no event will Sophic be responsible or liable to you or any other party for any damages of any kind arising out of or relating to the use of, misuse of and/or inability to use the Company’s website or Material. The information is directed only at persons resident in Canada. The Company’s Material or the information provided in the Material shall not in any form constitute as an offer or solicitation to anyone in the United States of America or any jurisdiction where such offer or solicitation is not authorized or to any person to whom it is unlawful to make such a solicitation. If you choose to access Sophic’s website and/or have signed up to receive the Company’s monthly newsletter or any other Material, you acknowledge that the information in the Material is intended for use by persons resident in Canada only. Sophic is not an investment advisory, and Material provided by Sophic shall not be used to make investment decisions. Information provided in the Company’s Material is often opinionated and should be considered for information purposes only. No stock exchange anywhere has approved or disapproved of the information contained herein. There is no express or implied solicitation to buy or sell securities. Sophic and/or its principals and employees may have positions in the stocks mentioned in the Company’s Material, and may trade in the stocks mentioned in the Material. Do not consider buying or selling any stock without conducting your own due diligence and/or without obtaining independent investment advice from a qualified and registered investment advisor.

Sean Peasgood

Writer