In a compelling essay called “Lost Roots: The Failure of For-Profit Couchsurfing” former couchsurfer Nithin Coca bemoans the death of what he regarded as a beautiful dream: people all over the world opening their homes to a social network of like-minded travelers in a way that had not been possible before the Internet, via a website called Couchsurfing.org.

Going back to its founding in 2004, Couchsurfers didn’t charge for opening up their homes. The network existed on trust and a spirit of openness and adventure, marred surprisingly rarely by stories of sexual predation, shakedown attempts and dirty hippies. Sporadic issues aside, Coca reserves his ire for what he regards as both the site and the community’s downfall. “I felt that once management put the values of venture capital funders over the organic, self-organized traveler base, and reorganized with a top-down, ‘start-up’ mentality, the fall was inevitable.” His article does not mention Airbnb.

The point at which it all went wrong in Coca’s eyes is when a site that had been essentially free and built by its volunteer users turned to venture capital for support. Couchsurfing headquarters was, after all, in San Francisco, and Couchsurfing’s new management decided to tap in to the new wave of start-up culture, attracting $22.6 million in VC funding. Within 18 months the CEO had stepped down, as well as a good deal of the staff, and Couchsurfing currently burns through approximately $80,000 per month while trying to figure out how to generate revenue as its original users abandon the site.

Going back to its founding in 2004, Couchsurfers didn’t charge for opening up their homes. The network existed on trust and a spirit of openness and adventure, marred surprisingly rarely by stories of sexual predation, shakedown attempts and dirty hippies.

Coca spends a lot of time enumerating the qualities that marked out “real” Couchsurfers from people he regarded as opportunists, hard-partiers, creepy dudes, and grifters, but saves his harshest criticism for the site’s new management, who’ve wrecked everything in their effort to fit in with the culture of Silicon Valley.

Facebook started out free, after all. It still is, in a very roundabout way, in the sense that you don’t pay money to join. And if Facebook represents the new “walled garden” ecosystem of the social Internet, Couchsurfing very much embodied the free, wild and open Internet of the 1990s. The two are also unalike in that Couchsurfing treats the Internet as a tool that enables people to get together in real time and space. Facebook enables people to get together while never having to see or talk to friends and relatives ever again. It’s not a tool for enabling experience. It is the experience.

Couchsurfing has been learning the hard way that turning your back on the people who got you to the point where you can attract millions in venture capital doesn’t guarantee you’ll retain that base. In fact, they can turn against you in a very ugly way.

But simply because Facebook is “free” doesn’t mean it has no loyalty problems.

Couchsurfing has been learning the hard way that turning your back on the people who got you to the point where you can attract millions in venture capital doesn’t guarantee you’ll retain that base. In fact, they can turn against you in a very ugly way.

Neil Parker, vice president of product marketing at market research firm Vision Critical, has noticed that Facebook has quietly implemented an invite-only Feedback Panel, which will collect candid comments from 10,000 users. As Parker points out, Facebook doesn’t lack data for insight. Even with all the data it collects from tracking user behaviour, from measuring audience reach and ad performance, “Facebook doesn’t know why we make the friends we make, why we post the pictures — embarrassing or benign — that we take, and why we go to the places we go. If Facebook doesn’t have enough data to answer the ‘why’, then who does?” Couchsurfing’s ethos inspired a worldwide social network of like-minded travelers. This meetup took place in Shiraz, Iran.

This insight reinforces the fact that while Big Data will certainly solve a lot of highly specific problems better than any human possibly could, there are some problems that cannot be explained in an infographic. It also goes a long way to explaining the difference between “free” and free.

Communities like Wattpad, Etsy, all of the dating websites, as well as freebie marketplace aggregators such as Craigslist or AskForTask, and social networks like Twitter and Facebook, all work nicely within the model of venture capital and the disruptive power of start-up culture. A company like Diaspora, however, which is an attempt to organize a non-monetizable alternative to Facebook, will not fit within that model. It’s not one-size-fits-all. Likewise with Couchsurfing.

And there is, of course, Airbnb, which is not free, but inexpensive and entirely unregulated, except where it is now being threatened by governments in New York and Quebec, with every other government on the planet watching how things progress legally in those places before taking action themselves.

There is still room, perhaps, for something like Couchsurfing. But its future can only be enabled by the Internet, the form it takes lies outside the models offered by venture capital.

As dodgy as Airbnb still seems to many, it at least offers a vastly slicker user experience and the sheen of respectability that reputation and a financial transaction bring, compared with the homemade groovy vibe of Couchsurfing. The difference between the two, though, illustrates the way that the Internet 1.0 way of life is slipping away from us, in favour of contained experiences, familiarity, and design thinking.

After the initial gold rush of the free Internet, things have changed in ways that make the Internet as unrecognizable to older users as watching a hockey game with clean, white, ad-free boards must seem to today’s viewers.

Some things have changed arguably for the better. The record industry? Good riddance. Others not so much. A recent essay begging writers to stop giving their work away for free, and unhelpfully referring to those who do as “slaves of the Internet”, met with a howl of protesting counterarguments. It’s no longer a question of whether to work for free, the argument runs, but how. For better or for worse, that battle has been lost.

Given the way things are shaking down with the sharing economy, the decision by Couchsurfing to take venture capital was its undoing. The insight gleaned from survey-style market research advocated by Neil Parker and Vision Critical, and only now being adopted by Facebook after years of tone-deafness to the needs of its users, could have saved Couchsurfing from making the mistake it did, with the result that we won’t be talking about Couchsurfing a year from now, because it’ll be gone.

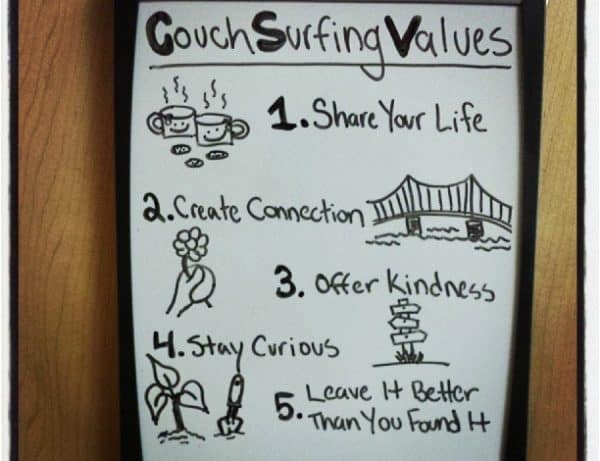

What differentiated Couchsurfing from Airbnb was that it was “real”, a grass-roots community of likeminded spirits who weren’t concerned about money. The moment they took that funding, the company’s language swapped out the terms “community” for “user base”, “user” for “customer” and “trust” for “transaction”. Airbnb already unproblematically does this, and Couchsurfing is now in the position of playing catch-up with its undifferentiated competition, having abandoned its old ways.

The difference between what Couchsurfing used to be and what Airbnb is now is the difference between the open and free model of Internet culture and the “walled garden” model that has taken shape over the last five-plus years.

There are things that start-up culture is good for. But like everything, it has its limits. There is still room, perhaps, for something like Couchsurfing. But its future can only be enabled by the Internet, the form it takes lies outside the models offered by venture capital.

____________________

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Share

Share

Comment