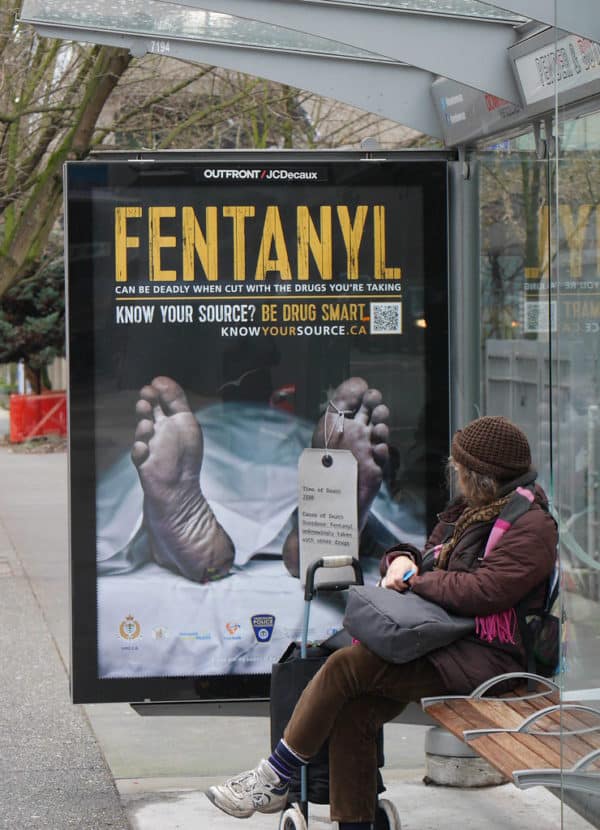

Taxpayers. Fentanyl: a confusing and sometimes maddening mix.

The opioid epidemic ravaging communities across Canada has reached crisis proportions. And while many agree that more needs to be done to prevent further deaths from drugs like fentanyl, the complexities of drug use and addiction are causing some to wonder about the role that Canada’s healthcare system —and thus, taxpayer dollars— should be playing in mounting a response.

The controversial question that continues to divide us: should harm reduction and prevention programs be paid for with public funds or are drug use and the hazards that it entails a person’s own responsibility?

The numbers are hard to fathom.

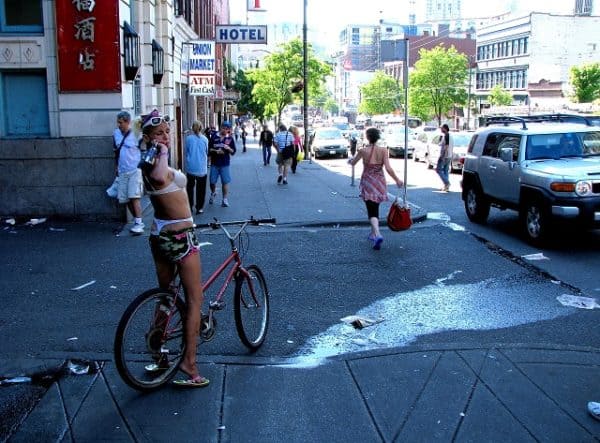

In 2016, more than 2,300 Canadians died of opioid overdose. Alberta saw 343 deaths and in BC, the Canadian epicentre of the fentanyl crisis, 914 people died of overdose. Last April, BC’s provincial health officer Dr. Perry Kendall declared the fentanyl crisis a public health emergency, while one year later, the deaths keep mounting, with the provincial toll for 2017 expected to exceed 1,400 at its current rate.

In Vancouver, as part of its measures to address the issue, city councillors voted this past December to increase public health emergency funding so as to better equip medical units and fire and rescue services to deal with the crisis. The motion, which came with a 0.5 per cent raise in property taxes for Vancouver residents, passed by a vote of 8 – 3, but dissenting voices were heard, both from council and from members of the public who felt that spending more money on the overdose problem —especially municipal dollars, when healthcare is primarily a provincial responsibility— is a questionable move.

Council remarks mostly stayed within the bounds of criticizing either the lack of public input before voting on what some termed the “fentanyl tax” or uncertainty over how exactly the new funds would be used. “It looks like a blank cheque to me,” said NPA Councillor Melissa De Genova, who voted against the increase.

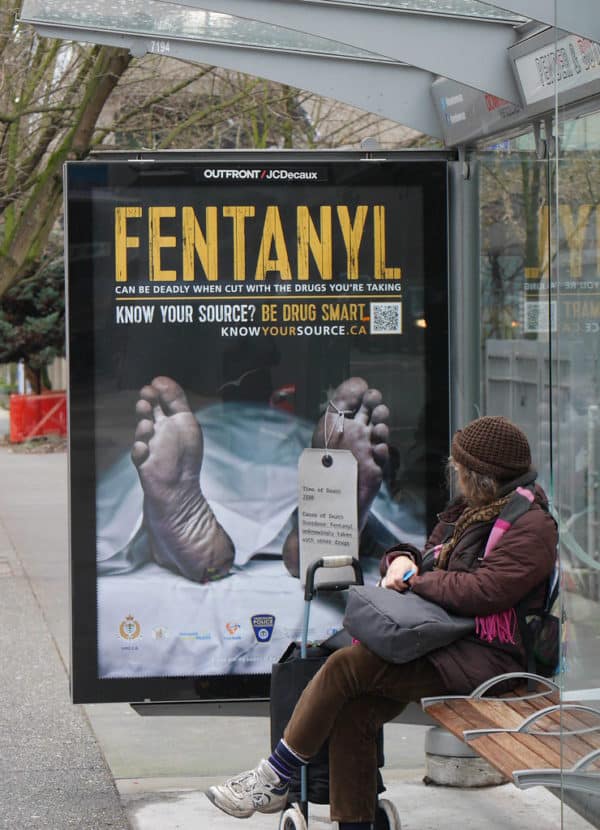

But the response from some BC residents was less candid.

A freedom-of-information request filed by the Georgia Strait looked at correspondence to the offices of the mayor and city manager during the second half of 2016 and found that of 81 emails reviewed on the issue of fentanyl, only three stated their support for the tax increase while many others expressed negative opinions towards drug users or towards the idea of the public paying for their actions.

“Why should property owners be penalized with a higher property tax to cover the costs of fentanyl overdoses,” read one of the emails.

That perception is one that Ann Livingston knows all about. As co-founder of the Overdose Prevention Society in Vancouver and a long-time frontline worker, Livingston is frustrated by what she sees as society’s discriminatory approach to dealing with drug addiction.

“It’s a bias, really,” Livingston said in conversation with Cantech Letter. “No other group in society gets treated this way.” Pointing to the “myth of bottoming out,” which contends that drug users need to reach rock bottom before recovery can take take place, Livingston says, “There’s no room for kindness in that approach. People think that cruelty is the best way to get them to stop using, but the evidence doesn’t bear that out.”

Researchers argue that the concepts of addiction and recovery have a social and moral context that should be recognized as affecting public strategies to combat addiction.

Dr. Peter Choate, assistant professor of Social Work and Disabilities at Mount Royal University in Calgary, says drug addiction needs to be viewed alongside other “primary” diseases like diabetes and heart disease. “One of the misnomers is that addiction is a moral choice, when in fact it’s a neurobiological disease,” says Choate to Cantech Letter.

Choate says that we need to approach drug addiction and attempts at drug recovery with the same mindset that we do these other diseases. “We don’t disparage funding for people with diabetes even, for instance, when they don’t follow through completely on their treatment plans, so why should we treat drug addicts any differently with regards to recovery?”

Meanwhile, health care advocates have been at pains to draw attention to the magnitude of the problem, urging that fentanyl deaths are not a niche issue affecting only those on the fringes of society. It’s been pointed out, for instance, that the opioid crisis is now taking more lives than did the ADIS epidemic at its peak.

“Drug users experience profound stigma and neglect,” says Katrina Pacey of Pivot Legal Society, a poverty and marginalized persons advocacy group in Vancouver, to Cantech Letter. “If these astonishing death rates were impacting any other population of Canadians, we would see immediate action. Instead, simple health measures like supervised injection, naloxone, and addiction treatment options have been slow to come online due to government inaction and lack of public support.”

Pacey says that federal and provincial governments need to make a “meaningful investment” in addiction services, including supervised consumption programs, prescription heroin and drug checking services to all people who use drugs so that they can find out what’s in their supply. Also, the criminal code needs to be amended, says Pacey. “The federal government should immediately take steps to amend Canada’s criminal laws to decriminalize possession of drugs for personal use,” says Pacey. “This is a key step in reducing the criminalization and stigmatization of drug users.”

As far as the extra cost to taxpayers goes, Livingston says that programs for drug users are an economic no-brainer. “One night in prison costs $200, an ambulance costs way more. So, if you really want to waste money, don’t spend any on drug users,” says Livingston.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Share

Share

Comment