Times are tough in the news media racket. Not only has print journalism been gutted by losses in advertising, leaving companies scrambling to compete in an increasingly digital and diversified landscape, but the very idea of mainstream news is taking hits left and right (mostly right) as a seemingly growing section of the public professes its distrust of established news sources.

Gallup polls suggest that only 40 per cent of United States citizens feel that their mass media sources are reporting the news “fully, accurately and fairly,” while in the United Kingdom, polls show that the most-read newspapers are also the least-trusted. More than ever, news sources are forced to compete with a range of alternatives from blogs and social media platforms to the dreaded fake news sites. Top that off with a US commander-in-chief who regularly stokes the fires of distrust, going so far as to call established media organizations “an enemy of the American people,” and you have a not just a crisis in confidence but, to get technical, a real (expletive) mess.

Take fake news, which won its moment in the spotlight after news (yes, real news) broke that online stories, full of fraudulent claims but attempting to appear legitimate news nonetheless, were being circulated on social media platforms in the run-up to November’s US presidential election. The thought that such stories might have influenced voters sent a shock through the collective consciousness. It also, eventually, prompted companies like Facebook and Google to start trying harder at weeding out false and intentionally deceptive stories and sites.

But how do we best filter out the fake news from the real news? Famously, a B.S. Detector plug-in was created for Facebook (and later blocked by the company) which professed to alert people to unreliable news sources. Facebook is also reportedly working with news outlets in France and Germany to make sure that fake news stories on Facebook relating to their respective upcoming elections don’t get passed off as real.

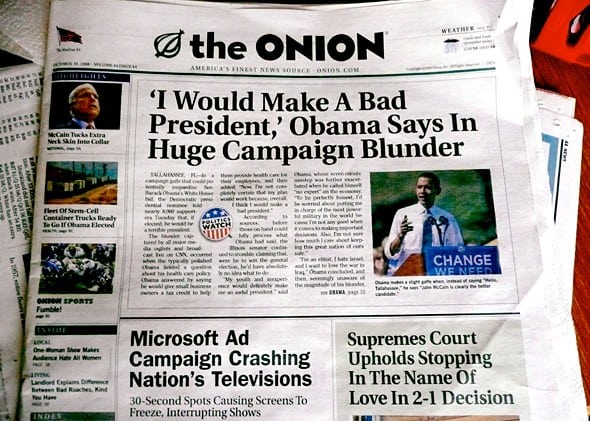

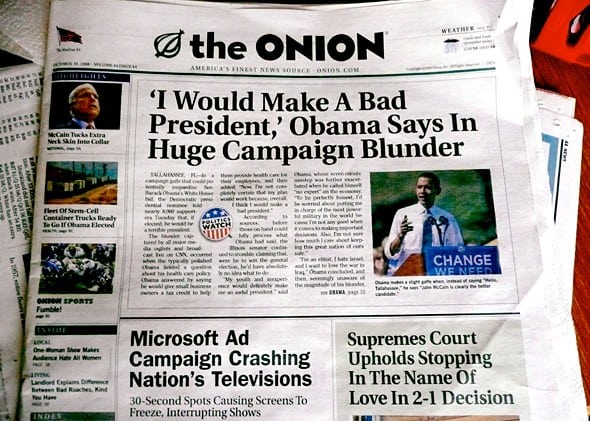

But now, what about an even narrower corner of the media puzzle: satirical news stories? In the United States, they have The Onion; in Canada, there’s The Beaverton. Both organizations attempt to bring the funny in part by putting on the dressing of a real news service. How do we tell —and more precisely, how would an algorithm tell— the difference between a Globe and Mail piece on PM Trudeau’s winter vacation and one by the Beaverton?

Researchers at Western University in London, Ontario, are attempting to address this very issue, starting by getting to the bottom of what counts as satirical news. In essence, they say, where other types of deception (such as that in fake news) really try to “win you over” into thinking they’re telling the truth, at some point along the way, satirical news items (the good ones, at least) always let the reader know it’s a gag.

“(Satire) was something we could really understand very clearly in terms of linguistic properties,” says Victoria Rubin of the Faculty of Information and Media Studies at Western in a press release. “We collected a large data set of The Onion as opposed to The New York Times, and Toronto Star, as opposed to The Beaverton, and we tried to find the differences.”

Through their work, the team identified five parameters for distinguishing satirical from real news pieces: a high prevalence of absurdity, humorous elements, long sentences, negative affect and punctuation style.

The researchers then created their own homemade satire detector (soon to be available online for the public to play with), which when tested turned out to be pretty spot on in picking the jokes from the facts: the detector proves accurate 80 to 85 per cent of the time, a number the team hopes will only go up the more the program is developed.

Rubin says that there is applied element to their research, as well, since there may be a need for automatic satire identifiers to help alert people of its presence.

“Most news are formatted alike and there is no clear visual distinction between a new piece from The New York Times and The Onion, for example,” says Rubin. “If the source attribution is unclear or its credibility is unknown, news readers might mistake a news parody for legitimate news.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Share

Share

Comment