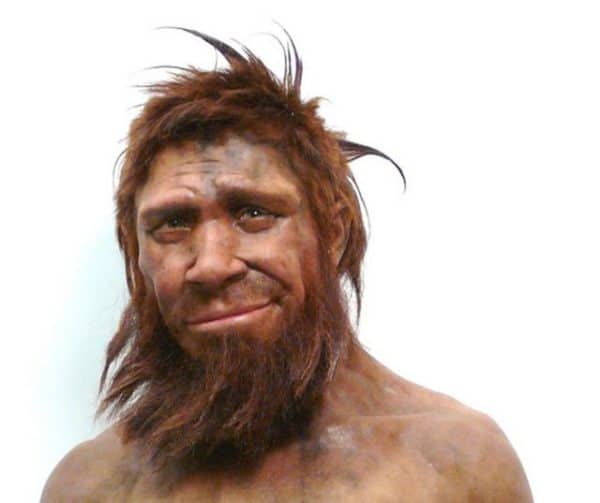

The rehabilitation of the Neanderthal image continues.

The rehabilitation of the Neanderthal image continues.

Authors of a new study of bone tools and beads found at the Grotte du Renne archaeological site in Arcy-sur-Cure, France, have confirmed that rather than being the leftovers of early modern humans, the controversial artifacts from Central France at the are likely Neanderthal in origin.

The Neanderthal line of genus homo lived in Europe and Asia between 400,000 and 28,000 years ago, and, during the final 10,000 years they lived alongside homo sapiens, competing for the same food sources and interbreeding with early humans, all before being wiped out by homo sapiens and their “superior” tool-making smarts.

Or so the story goes.

Jewelry making Neanderthal had the brains to create…

But at the Grotte du Renne and other archaeological sites around Europe, the battle between Neanderthal and homo sapiens wages on, as scientists debate the lineage of old bone artifacts, jewelry and tools to find out who had the brains to create the ancient items.

First discovered in 1949, the Grotte de Renne has produced a unique array of artifacts dating from approximately 40,000 years ago, alongside some Neanderthal remains. But early suggestions were that there had been some displacement of evidence over the years, with experts arguing that the beads and tools were likely transported to the cave by early homo sapiens and then somehow got mixed up with the Neanderthal remains.

Now, in a new study in the journal Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences, a research team led by scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, has brought forward what they see as conclusive proof of the Neanderthal origin of the tools and beads in question – and by the same token adding more grist to the argument supporting Neanderthal intelligence.

Previous attempts using DNA analysis to determine the lineage of bone fragments found alongside the ancient artifacts had proven unsuccessful, due to the lack of DNA available in the fragments. So this time, the researchers turned to protein analysis, attempting to identify the owners of the bones by the chemical composition of the collagen found in the connective tissue between bones.

It worked. The team found evidence of an amino acid called asparagine which had previously been connected to Neanderthal remains at other sites, thus conclusively dating the Grotte du Renne bone fragments as Neanderthal.

“For the first time, this research demonstrates the effectiveness of recent developments in ancient protein amino acid analysis and radiocarbon dating to discriminate between Late Pleistocene clades,” says Matthew Collins, archaeologist from the University of York in England and co-author of the new study.

The demise of the Neanderthal is still a debated topic, with evidence suggesting that because their disappearance from Europe and the Mediterranean between 45,000 and 43,000 years ago roughly corresponds with a change in climate (from cold to colder) the Neanderthal, although equipped with a sturdier, stockier frame than the homo sapiens, was unable to withstand the chillier climes.

Evidence suggests that Neanderthals did not create their own fires nor did they build structures in which to live. And as far as clothing goes, a new study from Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, B.C., looked at animals remains found near Neanderthal and homo sapiens sites and argued that the Neanderthal likely wore cape-like clothing while homo sapiens were decked out in fitted, fur-lined clothing.

The sartorial difference was quite possibly enough to usher in the extinction of the Neanderthal, so goes the contention, who on increasingly cold days wouldn’t be able to stay out to hunt for as long as would the well-clad early human.

“It might seem fairly small, but that could significantly enhance early modern humans’ ability to bring down a deer, and that means a difference in terms of calories,” says study author and paleonanthropologist at Simon Fraser, Mark Collard. “Evolution is typically a lot of small differences leading to big differences longer term.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Share

Share

Comment