While technological solutionism promises to solve every problem of modern life, it has yet to get around to dealing with one of our most intractable problems, food waste, which amounts to about $107 billion per year in Canada, according to the Value Chain Management Centre.

While technological solutionism promises to solve every problem of modern life, it has yet to get around to dealing with one of our most intractable problems, food waste, which amounts to about $107 billion per year in Canada, according to the Value Chain Management Centre.

It is already bad enough that household waste alone accounts for $14.6 billion of that figure annually, but waste on an industrial scale is responsible for keeping perfectly good food out of the mouths of Canadians, basically for frivolous reasons, which could easily meet the needs of society’s most vulnerable people, not to mention the environmental and economic benefits that would accrue if we managed to develop a cohesive strategy to do something about it.

The question is, what incentives are there for anyone to do anything about interrupting the status quo when it comes to the problem of food waste?

In 2010, a report by the Value Chain Management Centre, called “Food Waste in Canada”, followed by a 2013 report commissioned by Guelph, Ontario’s Provision Coalition, called “Developing an Industry Led Approach to Addressing Food Waste in Canada”, both came to the conclusion that the annual cost of food waste in Canada amounted to $27 billion.

In 2014, the Value Chain Management Centre revisited their initial report with new insights and revised the quantifiable value of food waste in Canada upward a full 15% to $31 billion, adjusted not by an actual increase in food waste but using new information that was unavailable to them in 2010.

That revised report, though, adds that “The true value of food waste is much higher,” since even their new estimate excludes institutional food waste (hospitals, prisons, and schools) and most of the travel industry.

Furthermore, accounting for the cumulative cost of waste associated with food production (energy, water, land, labour, capital investment, infrastructure, machinery, transport, etc.), the actual figure “really equates to $107 billion.”

To put $31 billion into some context, it is approximately 30% of the value of what the Canadian agriculture and agri-food system (AAFS) generated in 2012, it’s 2% of Canada’s GDP in 2013, it’s more than Canadians spent on food purchased from restaurants in 2011, it’s more than two-thirds of the value of all Canadian agricultural and agri-food exports ($43.6 billion) in 2012, it’s slightly below the value of all Canada’s agricultural and agri-food imports ($32.3 billion) in 2012, and it’s higher than the combined GDP of the 29 poorest countries.

In short, it’s a colossal problem. If the idea of setting the equivalent of 2% of Canada’s GDP on fire in a public square, or just using the money as field mulch, upsets you, then the existing problem should also upset you.

While the problem of food waste is a problem for everyone, it disproportionately affects farmers’ bottom lines, according to the 2014 “Food Waste in Canada” report, which says, “Food waste can impact farmers’ profitability more than downstream businesses, because their position within the value chain makes them least able to penalize their suppliers if their own or their customers’ operations are inefficient.”

The supply chain is long and complicated with plenty of opportunity for loss and damage, with every lost item carrying a cost that must be borne by retailers and then passed along to consumers, adding approximately 10% to your food bill that doesn’t need to be there.

Typical net margins for produce are 8% to 15% for meat, meaning that a retailer has to sell 15 to 20 items for every item lost in order to break even, given that grocery retailers’ operating profit margin for supermarkets (operating revenue minus operating expenses and costs of goods sold) is typically around 1.6%.

There are other factors among the various actors in the supply chain, other than just waste that exacerbates the problem, including slim profit margins, adversarial relationships between competitors, and uncoordinated value chains.

Even so, waste remains a big problem that society has yet to solve, despite the fact that technology has promised to make our lives more or less frictionless.

Food waste is the equivalent of 2% of Canada’s GDP in 2013, more than Canadians spent on food purchased from restaurants in 2011, and higher than the combined GDP of the 29 poorest countries.

On a hopeful note, there is an ad hoc group of interesting companies, industry groups and software developers across the country who are tackling the issue in their own way.

But there is no cohesive strategy, whether from industry or government or community groups, to coordinate efforts in such a way as to make a meaningful dent in the problem, much like the act of household recycling exists mainly to make people feel good while having a negligible impact on actual environmental problems.

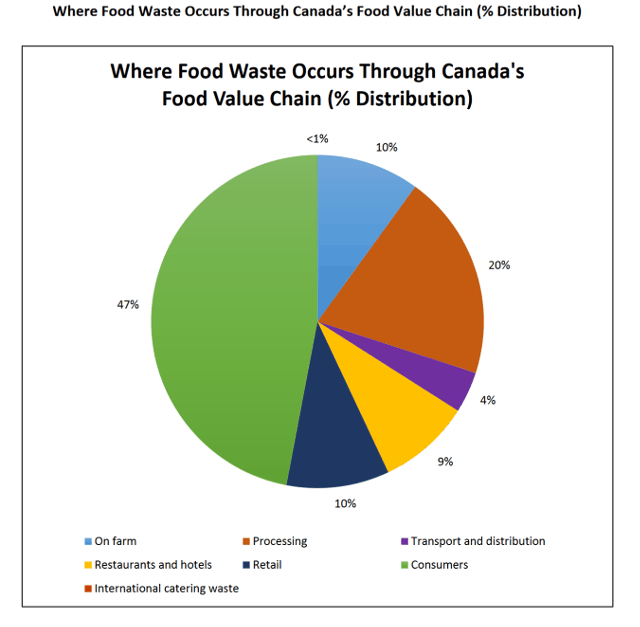

At the Processing & Packaging level, where roughly 18% to 20% of losses occur, a coalition led by Ippolito Fruit & Produce, Riga Farms, EarthFresh Foods and Amazing Grains is using hyperspectral chemical imaging technology to sort leafy greens, carrots and potatoes for production line grading, a technology developed by Ontario-based P&P Optica.

In the Maritimes, Moncton-based Fiddlehead has partnered with food giant McCain’s to implement a data-driven platform for providing more accurate demand forecasts, a problem which affects the Processing & Packaging category, as well as Retail which accounts for 10% to 11% of total food losses.

A team of University of Guelph researchers has developed a nanotechnology-based spray using a natural plant extract called hexanal, which prevents fruit spoilage.

While these stories and the people behind them are worth celebrating, it’s also worth pointing out that the problem is huge and complicated enough to require a level of coordination that would be something like putting society on a war footing to solve meaningfully.

Food waste involves not only problems throughout the value chain, but also requires providing incentives for consumers to alter their behaviour, much like drunk driving campaigns of the 1980s made the previously socially acceptable act of driving while loaded a social taboo.

The French government has set a target to reduce food waste by 50% by 2025, partly by forbidding grocery stores from destroying unsold food and giving it to charity instead.

Solving the problem of food waste should not only be a “feel good” measure.

Solving this problem will have very real benefits, both social and economic, for businesses, for which the total cost of waste along a value chain can exceed their combined profit margins, as well as for consumers, who can avoid paying what amounts to a 10% food waste tax, and for food producers who can reduce operating costs by 15% to 20% and increase profitability by the equivalent of 5% to 11%.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Share

Share

Comment