When we think of the future of cities, especially when we think of traffic in the city, we tend to envision a Jetsons future, with cars flying around ferrying people to where they need to go.

When we think of the future of cities, especially when we think of traffic in the city, we tend to envision a Jetsons future, with cars flying around ferrying people to where they need to go.

Miovision, a Kitchener-Waterloo company with deep roots in the University of Waterloo’s Engineering program, probably knows more about how that future is likely to pan out than any other group of people on the planet.

As Miovision CEO Kurtis McBride puts it, the future is a slow from-the-ground-up process, adapting previously existing infrastructure into new technological paradigms, and not the wholesale redesign favoured by companies who tout, and stand to profit most from, the Internet of Things.

McBride started the company with Tony Brijpaul and Kevin Madill while finishing an Engineering Masters degree at the University of Waterloo, counting cars at a Toronto intersection for a traffic engineering company.

Halfway through that Masters degree, in 2005, Miovision was born.

Miovision has maintained close ties with McBride’s alma mater, recently partnering with two companies started by U of W students, Brisk Synergies and Ecopia Technologies, developers of a data analytics platform and an urban visualization technology, respectively.

So much of what gets publicized in terms of solutions relating to the Internet of Things or smart cities is dead on arrival because it intrudes into people’s lives or offends their sensibilities in a way that either creeps them out or makes them shrug.

Miovision, by contrast, is working in that category of technological innovation that’s likely to thrive because it’s a) useful and b) invisible.

When infrastructure gets smart, people don’t resent the new paradigm because they don’t even notice that it’s happened.

“There is stuff like that, where real-time sensor data is being used to optimize, maybe not in the sense that people would think about it, but in a localized sense,” says McBride.

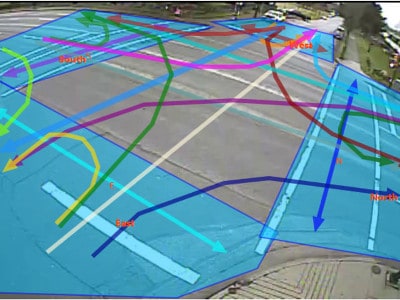

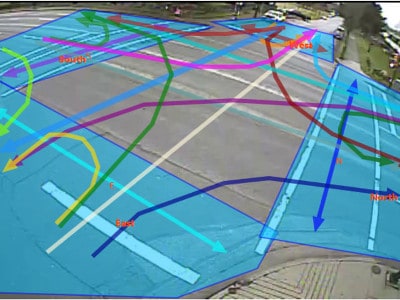

As the company moves beyond Miovision’s initial efforts, counting cars and modeling traffic, it is now poised, through its Spectrum line of products, to provide something for city infrastructure that no one else is doing: creating an operating system for the smart city.

That type of integration has implications for sensor-driven infrastructure, driverless cars, smart city technology and cleantech in general.

More importantly for Miovision, there are no other companies out there who have developed a solution for municipal infrastructure as it relates to traffic to the degree that they have over these past 10 years.

To celebrate Miovision’s birthday, people in the Waterloo area can stop by two locations, Communitech’s Area 51 at 151 Charles St. W. from 8:30-10:00, and the university Accelerator Centre’s Networking Area at 295 Hagey Blvd. from 11:30-1:00 p.m., to enjoy free coffee, snacks and a chat with one of Canada’s next great technology success stories.

Cantech Letter spoke with Kurtis McBride by phone.

So, Miovision is turning 10. Happy birthday.

Officially, I think we hit it this summer, but this is the official coming out party, I guess. I think officially, we incorporated the company in summer of 2005.

And were you a student at that time? What were the conditions leading up to the creation of the company?

I was doing my Masters at the time. I’d done a co-op job, and was in the Engineering program at Waterloo. You have to do six co-op terms, and one of my co-op terms I had done a stint at a traffic engineering company. I was doing some software development for them. But every once in a while they would show up, Friday afternoon in the room where all the co-op students were, and say, “Hey, we have this big traffic count we need to do on the weekend, and we’re short-staffed. Do you guys want to go out and make $12 an hour counting cars on Saturday?” I did that a few times, and sort of got introduced to it. But when I went back to school, I started to work on what became the company and then finished the Masters. So we started the company, I guess, about halfway through the Masters, after doing some work in this field.

And just for context, 2005, this is would have been two years before the arrival of the iPhone, so BlackBerry still enjoyed whatever market share it had and was riding high in Waterloo.

Yeah, to give you a sense of what was going on at that time, some of the software development that I was doing when I was working for this traffic engineering company, if you remember the Dell Axim, they were the ones that had the little stylus pencils that you used to use, the first attempts at a touch screen. So certainly it was early days for BlackBerry. There was no iPhone, there was no Android and there were still these little handheld devices that weren’t even necessarily phones at the time.

At what point did you realize you could go from counting cars in a co-op program to developing that into a business?

When I was doing it as part of a co-op job, I saw that there was a need for various people to be out there, paying attention to varying degrees, to do this type of data collection. When we started the company, there were questions in all of our heads, like, “Are these type of traffic counts done everywhere, or were they only done in this one place in Toronto?” To be honest, it was probably six months into the formation of the company before we really were convinced that this was a broader need that we had stumbled upon.

Mojio came out of the co-op programs at the University of Waterloo, and you’ve gone back there recently to partner with Brisk Synergies and Ecopia Technologies. How have the pilot projects that you’ve been developing with them been coming along?

They’re coming along well. They’re two very different applications, related but different applications, that we’ve partnered with them on. But we’re going to be taking both of them live. As you can imagine, these are both early-stage companies. So we took some nuggets of what they had and then basically specked out a way to buy the nuggets that we wanted, and that took a few months for them to build a use-case, essentially. But we’re trying to take them both into our products and launch one of them at the end of this year, so imminently, in the next few weeks, and then the other in the first quarter of next year. But they’ve both been really great teams to work with. It’s kind of fun being close to the start-up end of the spectrum again. But yeah, they’ve both been great to work with, and we’ll probably start to see some early production integration of their stuff coming up in the next one to three months.

“When I hear ‘smart city’, that’s how I interpret it. We’re moving to a software-driven paradigm.” – Kurtis McBride

Ten years ago, you were where they are now. But have you maintained close ties with your old school, or was it a recent decision to go back to the well?

No, we’ve tried to maintain those relationships in a few different ways. There’s a lab at the University of Waterloo called the Vision and Image Processing Lab. We’ve tried to be pretty involved with that lab. They do conferences and we present there, we post papers with them. We’ve actually hired a number of different students that have come through that lab. So we maintain pretty good relations with the university and those professors. And the other way we try to stay engaged, I do a lot of it and so does my business partner and some of the staff, is to do what we call “pay it forward” mentoring. There’s a lot of companies that are just getting out of the gate. The only way I’ve ever figured out how to pay back the guys that helped me in the early days is to have some of the same conversations that they had with me with the next generation of entrepreneurs. That’s not directly linked to the school per se, but that’s how I met both Brisk and Ecopia was just initially through a mentorship relationship. And then, as that matured, we started to see ways that their companies could help out with what we were trying to do.

Last time we chatted in February, you mentioned that you were working with about 500 organizations in 50 countries. Has that expanded since then?

We’re at about 650 customers right now. The number of countries is still probably in that range. It’s harder to add new countries. (Laughs.)

Ten years ago, the idea of the smart city was not on anyone’s radar. Now suddenly, in the last three years or so, municipalities are talking about it. Does that, and the rise of technologies like the driverless car and cleantech in general, have any practical uptake for you, as far as getting new clients in the door?

Yes and no. I always get a kick out of phrases like the “smart city” and the Internet of Things. We’ve been using cellular networks to connect devices for years, long before there was a thing called the Internet of Things. But now there’s a whole brand around the Internet of Things. And we’ve been using cloud software to service cities for almost a decade, and now that’s a thing called the “smart city”. So I get a kick out of it, because in a lot of respects all it did was wrap a catchphrase around some things that were already happening. That said, with any technology, you always have a technology adoption cycle. This is true of any customer, but inside of a public agency, you’re going to have early adopter personalities, the people who see the opportunity to take technology and make a difference. What the smart city and Internet of Things is doing is giving them more of a platform to pitch their ideas internally and get political buy-in, get budget buy-in, because the branding efforts that have gone into those phrases have created safe places for them essentially to go be innovative. So in that respect, I think it’s been helpful. It maybe speeded up some of our sales cycle. But at the end of the day, we do a lot of talks about the smart city, and you see a lot of companies out there talking past it. “In the future, this will be true.” But you don’t see a lot of tangible, practical projects that are spinning up out of that. But you see a lot of really expensive consulting engagements. So our focus is that it’s great that there’s this safe place where innovators can go and talk about the smart city, but ultimately the focus has to be on what we call “point solutions”, which is basically where we go in and understand a very specific problem and then apply a device and some software and communications to solve that specific problem. Either you’re saving the city money, or you’re helping to improve the experience of the citizen, because otherwise it’s just rhetoric, it’s just marketing.

Right. Those catchphrases ultimately come down to PR. The same dynamic applies to “the cloud”, which I just refer to as “someone else’s server”. Someone figured out how to put a bow on a practical thing, basically. But our progress towards what we want to see in the future is just this iterative process. It’s a very slow, painstaking path, which Miovision has been on all along. Speaking of which, last time we chatted you said that cities only calibrate their traffic lights every three to five years. Are we working towards a world in which traffic lights are optimized in real time? Or is that just science fiction?

No, we definitely are. There are degrees of that that are deployed in the world, even today. There are little magnetic loops in the ground, magnetic sensors, so if your car drives over one of those and you’re sitting in a left-turn lane, then some of those intersections might be smart enough to give you an advance left, versus if there’s no one there and it doesn’t give you an advance left. There is stuff like that, where real-time sensor data is being used to optimize, maybe not in the sense that people would think about it, but in a localized sense. But one of the things that the smart city PR has done is that there’s an openness or a willingness to non-traditional ways of getting data about what’s going on on the road, and to use that in the control schemes, which will ultimately lead to more optimization. There’s so much data. You can download Waze or Google Maps and see what the traffic patterns are as you drive along the road. That data is out there. It exists. But it isn’t integrated into the infrastructure. And there are really no examples of where that’s been successfully integrated. We’re on the cusp of acceptance, I think, of that technology.

Is there much overlap between the rise of driverless car technology and what you guys are doing?

I’ll throw out another buzz-phrase for you. One of the things that we’ve been starting to think about, the technology that we’re building for Spectrum, we think it has the potential to be what we call “the operating system of the smart city”. Essentially, if you think about the driverless car in the context of an urban network, in a city let’s say, a lot of people don’t necessarily know this but one of the ways that you plan out the signal timing at an intersection can come down to something that has nothing to do with moving traffic. There’s this concept called “access equity”. You own a store, and you want people to be able to turn left off the road to get into your store because that drives business into your store. If a whole bunch of cars queue up on the road at a red light and can’t turn left because they can’t get into the driveway with all those cars in the way, then it costs you money. You’re losing business. One of the things that happens at an intersection, different stakeholder groups might be queried and we might decide to run a less optimal timing plan for the driver to make sure that people can actually get into your store. The reason I bring up that example is that a lot of people look at the driverless car, and they think, “It’s just technology. It has to run inside the car,” for safety and to avoid crashing into things and whatnot. But we think that there’s a whole layer of public policy that’s implemented into the road networks that isn’t possible to implement inside a single car. It has to be implemented in a centralized way. So we think a lot of the stuff we’re building will lend itself to that migration. When you drive into Waterloo, your car will essentially register itself into the local policy administration layer and get inputs about how it has to behave in the network. And I think we’re pretty well positioned to do that kind of thing.

So eccentric policies like “No right turn on red” in Montreal and New York, the car senses that at the border.

Exactly. Your car downloads a set of parameters that says, “This is how you have to behave in this area.”

In a sense then, I guess the name “autonomous vehicle” is a bit of a misnomer. The vehicle becomes integrated into the grid as soon as you venture into that territory.

Yeah. There’s a lot of different visions about what the autonomous vehicle will be, but we’re pretty connected into the way that municipal planning and transportation planning works. Understanding the different nuances of how they make decisions on the network, I suspect that there will need to be that tight coupling between planning rules and autonomous vehicles. There’ll still be lots of things that are autonomous, like don’t hit other cars and obey the traffic signs and that kind of thing. But there will also be lots of stuff that needs to be downloaded, essentially.

“Either you’re saving the city money, or you’re helping to improve the experience of the citizen, because otherwise it’s just rhetoric, it’s just marketing.” – Kurtis McBride

What has the $30 million you raised last year allowed you to do?

We’ve grown our head count this year by about 30 staff. We’re just under 100 people now. So that was a big part of it. Beyond that, we’re starting to ramp up the go-to market strategy for our new Spectrum product line. Basically, we’re growing the business so that we can be the next Canadian success story.

What does the future look like, three to five years out, for you guys?

You mean, in terms of the world or the company? (Laughs.)

Right, I mean, part of the tension we’ve been tossing back and forth in our conversation is between people’s vision of the future, which is this Jetsons or TED talk idea of reality, versus the painstaking reality of actually building the future. Practically speaking, where can we get, in terms of Miovision’s area of specialization, in the next five years or so?

Let me give you an analogy of what I think is coming for city infrastructure in general, and then how Miovision fits into that. To go back 10 years, if you wanted a phone, you bought one of those flip phones. Then if you wanted something to watch movies on, you had a monitor. If you wanted something to do navigation for you, you bought one of those TomTom GPS systems. And the list goes on. Basically, we lived in a paradigm where every little piece of functionality that you wanted was in a different device. Fast forward to today, all of those things are available on your Galaxy Note. You have a cell phone, and you can watch movies on it. You can get Google Maps to give you directions. You can make phone calls. So we’ve moved from a device-equals-feature paradigm to one device with a whole bunch of software options that run on it. And the benefit to you, the consumer, is that the incremental cost of those features is close to zero. You just download another app, essentially. If you look at infrastructure, with all of the infrastructure devices that are out there that provide a function for the infrastructure, it’s the same paradigm as where we were 10 years ago with personal electronics. So if I want a sensor, I install one device, and if I want a smart control system for my intersection, different device. If I want communications, different device. We see a future where basically all of that gets consolidated into a single device. And then the limit is really just defined by how much software you deploy on that device. So the cost of functionality, the price performance for city infrastructure, goes down dramatically. Instead of having ten $5,000 devices, you now have one $5,000 device, and then your incremental cost of adding functionality is next to zero, because it’s software. So when I hear “smart city”, that’s how I interpret it. We’re moving to a software-driven paradigm. For Miovision, the neat thing, at least as it pertains to traffic, there’s really no one else in the industry that’s seeing and building that future. There’s a lot of incumbents who are locked in to their way of doing things. So we think we’re going to be pretty well positioned to help create that future. But the neat thing about that cell phone analogy I used is that not only do a few companies do really well in that paradigm, like the Apples and the Googles and even the BlackBerrys, but behind them is hundreds of other companies that can build on top of that. It’s a much more open environment. It’s an open ecosystem, where you can basically just leverage what they’ve put together and build your own value streams and deploy it really easily. We think we’re really well positioned to lead that charge to a software-enabled infrastructure paradigm. But we also think we’re really well positioned, if you look at the five to ten year time frame, to essentially build an application ecosystem, like an app store, for the intersection, in a way that’s never really been possible before.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Share

Share

Comment