A new wave of anti-tech sentiment has surfaced in the United States of late. America’s new tech puritans regard personal devices and social media as the next level of dangerous distraction for an already distracted populace.

But a cursory look at the history of innovation in America shows that these people are the mere unpolished descendents of those who decried the emergence of the automobile, the telephone and television.

They’re wrong. Again.

In the late-nineteenth century, American composer John Philip Sousa greeted the phonograph with a sneer, remarking that the invention would usher in “a marked deterioration in American music and musical taste.” He may or may not have been right, but the moment a genie is released from its bottle, there is no stopping it from its appointed rounds. Easy access to recorded music let white teenagers smuggle black music under the noses of their parents, teachers and priests, which led to dancing, social liberation, and all kinds of unsavoury pastimes. It’s not the technology itself that draws the sneer out of Sousa and people like him. It’s what people do with the technology.

But can there be anyone left who really wishes for a return to pre-modern times? Who thinks our lives have not been significantly improved by technology, in ways both material and otherwise?

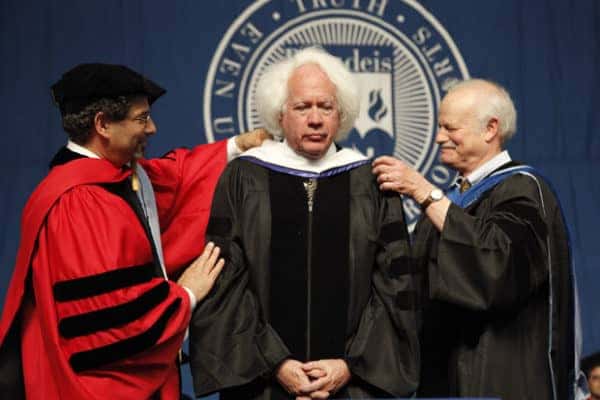

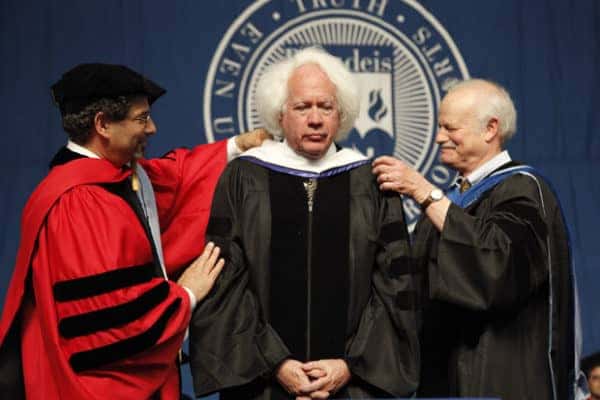

On May 19th, Leon Wieseltier, editor at the New Republic magazine, spoke at the commencement ceremony at Brandeis University. It went something like this: “…there is no task more urgent in American intellectual life at this hour than to offer some resistance to the twin imperialisms of science and technology.” He summoned his audience, like Spartacus leading a rebellion; “The machines to which we have become enslaved, all of them quite astonishing, represent the greatest assault on human attention ever devised: they are engines of mental and spiritual dispersal, which make us wider only by making us less deep.”

Can there be anyone left who really wishes for a return to pre-modern times? Who thinks our lives have not been significantly improved by technology, in ways both material and otherwise?

It’s possible that no cheaper applause was ever extracted from a more willing choir on the Brandeis campus than by Wieseltier on that day. But some don’t mind how they get the standing ovation, so long as they can hear clapping.

Contrast this obscurantism with American theoretical physicist Richard Feynman in New York City in 1966, speaking to a group of fellow teachers: “I have much experience only in teaching graduate students in physics, and as a result of the experience I know that I don’t know how to teach.” He then goes on to deliver a spellbinding account of how observing natural phenomena and following the scientific method restores one to a greater sense of wonder and awe in the world.

If Wieseltier were alone in his puritanical crusade to resist technological imperialism, he could be safely ignored. But he isn’t.

Pico Iyer, writing in the New York Times, reinforces the false distinction in a paragraph that could convincingly pass for satire.

“About a year ago, I flew to Singapore to join the writer Malcolm Gladwell, the fashion designer Marc Ecko and the graphic designer Stefan Sagmeister in addressing a group of advertising people on ‘Marketing to the Child of Tomorrow.’ Soon after I arrived, the chief executive of the agency that had invited us took me aside. What he was most interested in, he began — I braced myself for mention of some next-generation stealth campaign — was stillness.”

Iyer encourages us to buy into a fantasy: that somewhere there are people living better and more simply than we ever could, wrapped up as we are in our toys. That people are only happy when they manage to suffocate distraction and embrace stillness and switch everything off. That our lives are wrong.

Is reading poetry or meditating or paying close attention only possible in the absence of technology? Of course not. And for those who need to be made to concentrate, there’s a piece of software called Freedom. It’s the best $10 you’ll likely ever spend. But Iyer exhorts us, “But it’s only by having some distance from the world that you can see it whole, and understand what you should be doing with it.”

If not for scientific curiosity and technology to help us actually see the world whole and from a distance, we would all still believe that it is flat. Would you have guessed that the earth was round based on your own observations and life experience? Without seeing pictures of it from space and scientists such as Galileo and every scientist since showing you that it’s round? Be honest.

Iyer approvingly quotes 17th-century French philosopher Blaise Pascal: “Distraction is the only thing that consoles us for our miseries, and yet it is itself the greatest of our miseries.”

On May 1st of this year, the writer Paul Miller plugged back in after a year without the internet. He had unplugged because his life “lacked meaning” and he believed that the internet had “corrupted my soul”. After his experiment, he wrote, “So much ink has been spilled deriding the false concept of a ‘Facebook friend,’ but I can tell you that a ‘Facebook friend’ is better than nothing.”

The takeaway from Miller’s article is that he thought his problems were caused by his technology-fueled state of distraction. But it turned out that his problems were there waiting for him in the silence and the dark.

At the end of his commencement speech, Wieseltier invokes Marcel Proust, as if he has a greater claim than, say, a neuroscientist on understanding a writer who employed distraction (the Madeleine dipped in tea) in order to plunge himself and us into a fully drawn world of interiors.

Marcel Proust, if he were alive now, would be a Twitter whore. His whole life was spent watching others and commenting on their mores. It is quite likely that if Proust had an iPad with him in his sickbed instead of a pen and paper, he would have never written a word of “In Search of Lost Time” and instead died while chuckling at Grumpy Cat. Or he would have installed Freedom, stopped feeling sorry for himself and started working.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Share

Share

Comment