In 1992, RIM CEO Mike Lazaridis hired a thirty one year old Harvard MBA named Jim Balsillie as vice-president of business development. Balsillie invested $125,000 of his own money and obtained a 33% interest in the fledgling company. Two days later Balsillie asked RIM accountant Mike Vasilliou to produce a balance sheet showing how much the money had improved the company. But Vasilliou could show him nothing. The money was already out the door to cover overdue payables. Today, RIM’s Blackberry has become a household name and the company an unrivaled Canadian success story.Research in Motion has sold over 75 million smartphones -nearly half of those in the past year alone. Released just weeks ago Rod McQueen’s “Blackberry: The Inside Story of Research in Motion” is already a bestseller. The book is fascinating read and an important document of decades long “overnight” success story that RIM became. We sat down with author Rod McQueen to talk about the book. Oh, and that $125,000 that Balsillie invested? We don’t want to spoil the end of the book for you or anything, but in the end it worked out alright…

Nick Waddell: At the end of your book “Blackberry: The Inside Story of Research in Motion”, you describe RIM as taking “twenty five years to become an overnight success.” I, for one, didn’t realize the amount of contract and consulting work that RIM took on, particularly before the arrival of Jim Balsillie in 1992. RIM was involved with film editing equipment, they made giant LED signs for GM, high tech toothbrushes, even had a brush with the space arm. It strikes me that while Lazaridis had a lot of determination, getting into the wireless space must have been a real “a-ha” moment.

Rod McQueen: Mike would be the first to tell you there is no single “a-ha” moment. There is only an idea, persistence, bright colleagues, and a little luck along the way. In high school, he had a teacher who prophetically said: “Don’t get too hooked on computers. Someday the person who puts wireless and computers together is really going to make something.” The first few years of RIM, launched in 1984, were focused on a variety of products, none of them wireless. In 1987, while in Japan, Mike saw a wireless system that monitored vending machines and told drivers when the machines needed refilling.

At the time, in North America, wireless data systems were still in their infancy. By 1996, when RIM produced its first wireless e-mail device, known as the Bullfrog, the market remained tiny. Everybody was focused on cellphones and voice, not wireless and data. Even after BlackBerry was launched in 1999, only 25,000 subscribers signed up during the first year of availability. It took five years to get to one million subscribers; now RIM grows by one million new subscribers each month.

NW: RIM has a well deserved reputation for being a company that is run by its engineers and Jim Balsillie has a reputation, at least in the media, as being a bit of a bulldog. Yet there never seems to be a moment when The Company’s “engineer first” philosophy seems in danger of being reversed to a sales-first one. Is this a tribute to Balsillie? I think some people will be surprised how nuanced and subtle he appears in many situations in the book. He is broadly understood to be “the sales guy” but he never seems to push a sales agenda that interferes with the engineering agenda…

RM: Mike and Jim have been co-CEOs since 1993. I know of no other company that has made such a joint relationship work for so long. The duties are divided right down the middle so that Mike looks after engineering, research and development; Jim handles business, sales and finance. As Jim says, “I raise the money and Mike spends it.” The two don’t second-guess each other or look over each other’s shoulder. Still, when it comes to what Mike calls “bet the farm” decisions, he makes them. Such a decision occurred with the launch of the Pearl in 2006 when the trackwheel that had been on the side in previous models was replaced by the trackball in the center. “As soon as I played with the trackball, I said, ‘We’re doing it,’” Mike told me. “Those are the kinds of decisions that I reserve the right to make.” He also wanted the trackball lit. The engineers fought back with all kinds of arguments. “I just put my foot down and said, ‘This is what we’re going to do.’ I rarely pull rank; that was one of the times I pulled rank.”

NW: Even “The Donut Rule” stuff, the rule Balsillie made that anyone caught watching or talking about RIM’s share price had to buy donuts for everyone, strikes me as humble, humourous, and, dare I say “Canadian” leadership style…

Rod McQueen: The donut rule is famous. Chief Operating Officer Don Morrison was the highest-ranking officer I found who talked about share price during office hours, got caught, and had to buy donuts. Beyond such fun (but real) rules the leadership style and corporate culture is very interesting. I’ve never seen another like it during my thirty years of writing books about business. More companies should follow their open style. Even though RIM hires at least 1,000 new employees annually, every few months, the latest arrivals are gathered together to meet Mike and hear from him the company’s history, his vision, and where they are going together. Every Monday morning, Jim meets with a large group of people in Waterloo and via videoconference from around the world, hearing reports and exchanging real-time information.

As a result, everyone knows who the bosses are and what they’re thinking. There is no bureaucracy and no hierarchy. And everybody has a BlackBerry and that helps keeps all employees in sync. Moreover, every year 1,000 students from ten universities in the U.S. and Canada join RIM during work-term programs. Their presence and energy keep ideas bubbling up from within. If that’s a “Canadian” leadership style, more Canadians should follow it.

NW: Everyone agrees that Lazaridis is a technical genius, but I learned through your book that he is not the kind of genius that would be hard for sales people to work with or understand. This seems to be a key to achieving a sense of team throughout the company -all of RIM’s products are kind of “backward” engineered -Lazaridis thinks of the customer and the functionality of the product first and works from there. There are numerous examples of this in the book…

RM: Mike learned two important lessons while he was a student on a work term at Control Data in Mississauga, Ontario, where he saw how marketing people ruined an excellent engineering project. He resolved, first, to start his own business so he could be in charge and not have to kowtow to superiors, and, second, to honor engineers with innovative ideas. The launch of Pearl again provides an excellent example of that “backward engineering” you referred to. In 2003, RIM was doing well with business clients, including both large and smaller companies, but RIM knew they had to expand their markets to include consumers for the best growth prospects.

Mike put together a team to develop what became Pearl and met with them weekly during the three-year period to oversee progress. At the same time, Jim was streamlining the sales methods. RIM had been using both carriers and RIM’s own sales reps. Jim decided to focus solely on carriers because they already had multiple distribution outlets. Hiring sufficient sales reps at RIM made no sense.

Initially, signing contracts with the carriers was slow; RIM was only adding 20-30 new carriers a year. Jim ordered the process be turned into a cookie-cutter approach. The time taken to sign up a carrier was cut from six months to six weeks and RIM began adding 100 carriers a year. Now BlackBerry is available from more than 500 carriers in 170 countries. That period leading up to Pearl is just another instance showing how the two co-CEOs use their respective power appropriately to run their area and bring the mutual efforts together successfully.

NW: On page 108 there is a quote from Lazaridis that seemed to sum how his philosophy is embedded in the RIM culture and therefore in its products. He said “We develop from scarcity so we have to be disciplined”. Many people don’t realize that for a significant portion of its history RIM could not simply throw money at problems.

RM: The particular quote refers to the occasion when Intel was developing a chip for RIM in 1997. Just as RIM had a relationship with Bell South for the wireless network, RIM also worked with Intel which was spending its own money on developing a suitable microprocessor without any guarantee RIM would place an order for the results. These alliances with big U.S. companies were unusual for a small Canadian company with a few dozen employees. Clearly, Bell South and Intel recognized that RIM was onto the next new thing.

In discussions with both companies, when Mike mentioned scarcity, he was talking specifically about battery life. “Wireless is inherently constrained in terms of memory, power, and bandwidth,” he told the Intel team as he held a wooden mockup in one hand and a AA battery in the other. “Together, we’re going to make a little device that runs for twenty days on this battery, twenty-four hours, seven days a week. I’m going to show you how to do that.” He urged them to try something they’d never done before: decrease performance and go for lower power. The Intel team devised a slogan: “Have you saved a milliwatt today?” They put the words on banners throughout their labs and offices. At one point, Intel sent Mike a functioning version for testing. He was stunned by the results. “I plug it in and I can’t believe how little current this thing is drawing,” Mike told me. “It was like, twelve microamps, which is almost nothing. Two pieces of wire put together with a little bit of saline would generate twelve microamps.” It was another successful step toward BlackBerry – all based on being mindful of scarcity.

NW: The Globe and Mail took a minor shot at the book for not being critical enough, but it struck me that the access you were granted gave you insight that the author of a muckraking tell-all would never get. What kind of access did you have to senior management and to the RIM campus when you were writing “Blackberry”?

RM: The Globe said that I should have written more about stock option backdating at RIM. I thought that particular issue had been fully covered by the media. To me, the patent battle with NTP that cost RIM $612.5 million was far more interesting. I spent a full chapter explaining the intricacies of that issue.

I had not previously met the Globe reviewer in question but I did happen to meet him ten days after the review ran. Once we were introduced, the first word out of his mouth was “Sorry.” What an odd thing, I thought. Denounce a book and then apologize to the author. The book has been a great success, despite his review. For me, selling well is the best revenge. I’ve written award-winning books about empires, companies, and individual businesspeople that have failed: The Eatons, Confederation Life, and Edgar Bronfman Jr. This time I wanted to write about a success story. Waterloo-based RIM was an obvious example, just an hour up the road from where I live in Toronto. Initially, access was difficult to obtain and took a year to arrange. Everyone at RIM was busy so the interviews were stretched out over the next three years. In the end I interviewed Mike and Jim for a total of eight interviews lasting 2-3 hours each. I also interviewed all the other senior executives at least once as well as several people further down in the organization who had numerous patents to their name.

In all I probably did 100 interviews with people from RIM, Bell South, Intel as well as other observers and participants in the wireless business in order to understand fully the development of what has become Canada’s best known global brand. During my final interview with Mike, he said, “Aren’t you glad this book took you so long? When you first started, we were just a niche product. Now, we’re number one in North America.” I couldn’t agree more.

NW: A subject that comes up a lot on The Dollarton Cantech Letter is “tech clusters”. We’re unabashed supporters of Canada moving up the value chain and promoting more technology based businesses. These always seem to come from regional “Silicon Valley” style flare-ups. We have seen flourishing examples of this perhaps twice in our history; in Ottawa with the Nortel era, and with what has gone on with RIM in Waterloo. In your opinion what are the elements necessary? Do you think basing the community around a university is a key?

RM: In the case of Ottawa and Kanata, the National Research Council, Bell Labs and Nortel were influential in creating a tech cluster in the National Capital Region. I am confident that in time something even bigger will occur in Waterloo. The University of Waterloo and Wilfrid Laurier provide skilled graduates just like Stanford in California’s Silicon Valley. Keeping our best and brightest in Canada is crucial. After all, as taxpayers we help young people get an education. Why not keep them here after graduation? As for location next to the university, Mike has said, “I built the refinery next to the gold mine.” Stanford’s involvement with start-ups has a 70-year advantage over Waterloo. Hewlett-Packard was founded in the 1930s and has been followed by scores of other companies that became big tech names. For a long time not that many people left RIM to start their own firms but recently I’m hearing about employees who have peeled off to pursue their own dreams. Couple that entrepreneurial activity with the Accelerator Centre and the Research + Technology Park in Waterloo and I think in 50 years Waterloo –†and Canada – will be a very different place.

Imagine if Canada had ten companies like RIM. We’d feel as proud every day as we did that Sunday when Canada beat the U.S. at men’s hockey in the Olympics.

NW: It’s hard to fathom that Mike Lazaridis has trouble getting the government to contribute to projects that he literally donates hundreds of millions of dollars of his own money to. In Chapter 7, you recount how John Latham, RIM’s director of business development, landed a $4.7 million grant from the Ontario Technology Fund. I think that investment worked out pretty well for Canadians….

RM: Mike was talking about projects such as the Perimeter Institute where he invested $150 million yet government support was slow. Mike and Jim have now invested about $400 million in new institutions in Waterloo. Government money and private donors have put the total at $700 million. Over the years, RIM itself had helpful government support. The first money Mike raised to launch his business was $15,000 from his parents. At the same time he also received a matching amount from a Government of Ontario program called Student Venture Loan. That, too, worked out pretty well. More recently, RIM received money from Technology Partnerships Canada, a Department of Industry program for R&D, and benefited from the Scientific Research and Development investment tax credits. Since 2004, RIM has sought no further government assistance.

NW: Last question. What’s the future for RIM? Can they keep their competitive advantage?

RM: I think the future for RIM is very bright. In 1997, RIM had 100 employees, today there are more than 12,000. Last year, Fortune named RIM the fastest-growing company in the world.

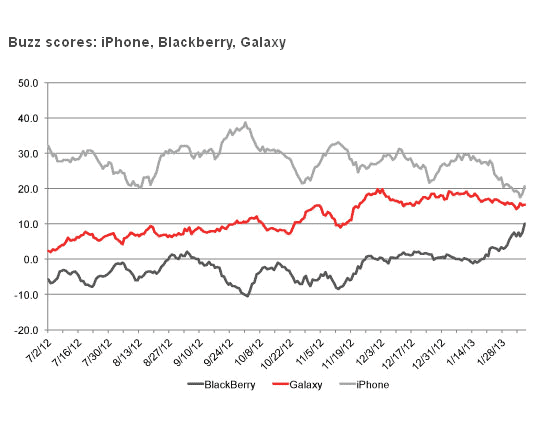

Over the years there have been numerous naysayers who predicted the demise of RIM because of various BlackBerry “killer” devices that never amounted to very much. At the moment, RIM has 43 per cent of the smartphone market in North America. iPhone ranks second with about half that; everyone else has 15 per cent or less in market share.

The plain-vanilla cell phone is the most popular consumer electronics device of all time. As those billions of users upgrade to smartphones over the next 5-7 years, I think RIM and BlackBerry will continue to be a leader. They are certainly well positioned to do so. As Canadians, we should all wish them well.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Share

Share

Comment