Does it matter what time it is when you get bitten by that bug? Apparently so, say scientists with the Douglas Mental Health University Institute at McGill University in Montreal who conclude that the severity of infections caused by bites from sand fleas can vary depending on the hour, finding that peak levels occur during the day to night transition period.

Does it matter what time it is when you get bitten by that bug? Apparently so, say scientists with the Douglas Mental Health University Institute at McGill University in Montreal who conclude that the severity of infections caused by bites from sand fleas can vary depending on the hour, finding that peak levels occur during the day to night transition period.

Science has learned a lot about the human body’s circadian rhythm and how it regulates processes like mood, hunger, heart function and mental alertness. The clearest example is the sleep-wake cycle, which is linked to the yearly path of the Earth around the Sun, making us sleepy during the night and wakeful during the day —and thus, causes a range of negative health effects for people doing shift work or experiencing jet lag, for example.

Our immune systems are also impacted by daily rhythms, as chemical compounds in our bodies like cytokines and immune response cells such as macrophages and neutrophils. Studies have shown that animals, including human babies, receiving vaccines will develop stronger or weaker immune responses depending on the time of day.

Parasitic infection: our immune responses are greater in the early evening…

Infections, too, have varying impacts at different hours, with research showing that our immune responses to bacterial and viral infections are strongest in the early evening, due to a greater presence of inflammatory cells.

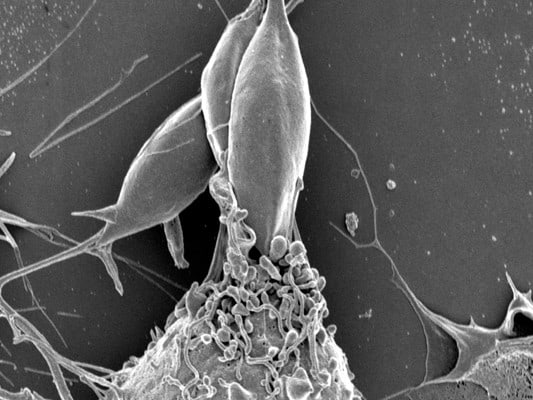

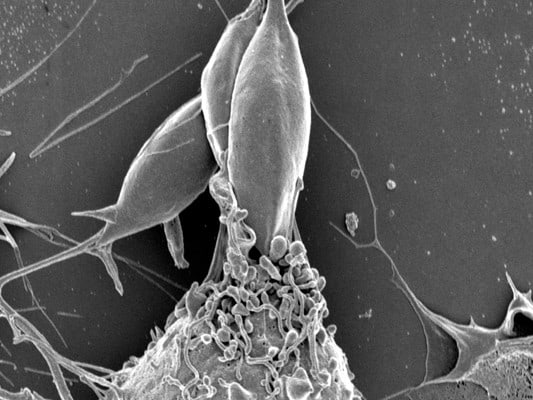

The new study extends that phenomenon to parasites, such as Leishmania, which is commonly transmitted by the female sandfly, producing leishmaniasis, a disease that can result in skin sores and, in more serious cases, damage to internal organs like the liver and spleen. Only a small number of those infected by the Leishmania parasite develop the disease, yet the World Health Organization estimates that up to one million new cases of leishmaniasis occur worldwide every year, with 20,000 to 30,000 deaths occurring annually.

To test the relationship between protozoan parasite infection and circadian rhythms, researchers injected Leishmania parasites into mice and observed that the day-night transition period turned out to result in the strongest bodily infections.

“We already knew that viral and bacterial infections were controlled by our immune system’s circadian rhythms, but this is the first time this is shown for a parasitic infection, and for a vector-transmitted infection,” says professor Nicolas Cermakian of McGill’s Department of Psychiatry and researcher at the Douglas Institute, in a press release.

But why would the sand flea parasite be most effective precisely at the time when our bodies’ defence mechanisms are running at peak capacity? It turns out that Leishmania are adept at co-opting neutrophils and macrophages to act as host cells to carry them throughout the body, meaning that a greater immune response will effectively result in a stronger attack on the body by the invading parasite.

The researchers say that learning more about the relationship between circadian rhythm and infection will help inform therapeutic and prevention methods. “Understanding the timed regulation of host-parasite interactions will allow developing better prophylactic and therapeutic strategies to fight off vector-borne diseases,” say the study’s authors.

The new research is presented in the journal Scientific Reports.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Share

Share

Comment