New technology is giving astronomers the boost they need to find life on other planets.

New technology is giving astronomers the boost they need to find life on other planets.

A recent study published in the journal Science Advances describes a new method for gauging the surface gravity of stars. And researchers say this will help to identify planets within habitable regions in outer space – the so-called Goldilocks Zones.

“If you don’t know the star, you don’t know the planet,” says the study’s co-author Jaymie Matthews of UBC’s Department of Physics and Astronomy.

Described as the “timescale technique,” this new approach looks to improve upon planet detection methods by more accurately measuring the size and mass of stars (and thus their gravitational pull) through an analysis of variations in a star’s brightness over time. Previous methods of detection relied exclusively on photometric measurements, which are less reliable the more distant (and faint) the star’s light source. According to the study’s authors, the timescale technique “can measure surface gravity in stars for which no other analysis is now possible.”

This comes on the heels of last year’s confirmation that over 1000 exoplanets (planets outside our solar system) have now been identified, a dozen of which are thought to be within habitable regions around stars. Top among them is Kepler-452b, confirmed by NASA to be a planet 60% larger than Earth and 1,400 light-years away, orbiting a star of approximately the same temperature as the Sun.

Our technique can tell you how big and bright is the star and if a planet around it is the right size and temperature to have water oceans and maybe life.

These new discoveries are all due to the Kepler mission, launched by NASA in 2009 to aid in the detection of Earth-like planets within our Milky Way galaxy. The Kepler spacecraft monitors the light intensity of over 145,000 stars – still only a tiny fraction of the 200 billion stars in the Milky Way.

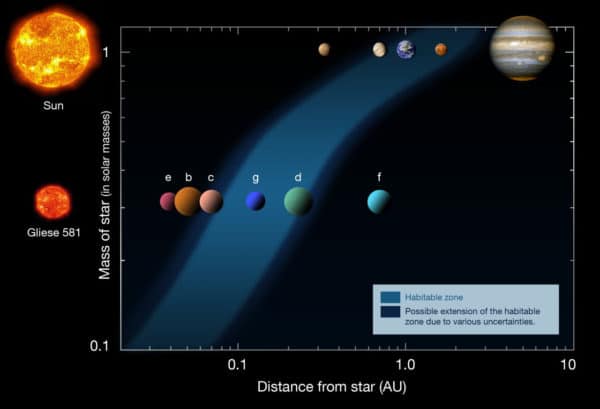

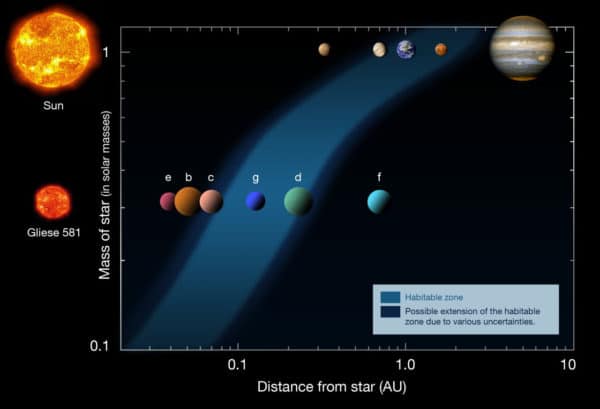

The end goal of this search is to identify exoplanets within the Goldilocks Zone – areas around stars that are suitable for sustaining life (as in the fairy tale, they’re “not too hot” and “not too cold”). What counts as a habitable zone depends on a planet’s distance from its star but also on the luminosity of the star, both of which will go into determining whether or not liquid water is present. And, along with liquid water, it is theorized that in order to sustain life a planetary body must also possess an active core and be of a size and density able to support an atmosphere.

In our solar system, liquid water has been observed or theorized to exist on a number of bodies – on Enceladus, a moon of Saturn, on two moons of Jupiter, Ganymede and Europa, and, most recently, liquid water has been detected on Mars.

Of the new study, Professor Matthews says, “Our technique can tell you how big and bright is the star and if a planet around it is the right size and temperature to have water oceans and maybe life.”

The study to find life on other planets was headed by University of Vienna’s Thomas Kallinger and involved a team of astronomers from Canada, Germany, France and Australia.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Share

Share

Comment