Gord Downie’s brain cancer is untreatable but new research is showing promise

Gord Downie’s brain cancer is untreatable, but there is a glimmer of hope for future patients.

Gord Downie’s brain cancer is untreatable, but there is a glimmer of hope for future patients.

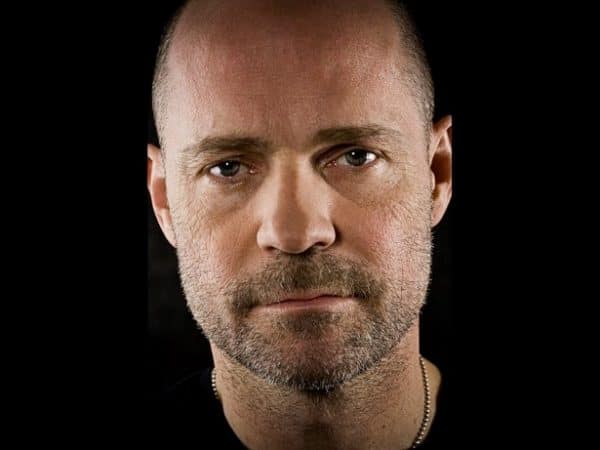

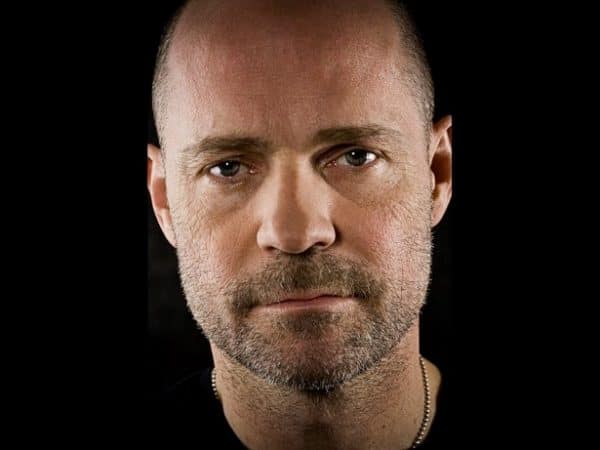

Kingston, Ontario, band and Canadian rock icons the Tragically Hip launched their 15-date summer tour in Victoria, BC, this past weekend, performing in support of their 14th studio album, Man Machine Poem, and starting on what for the group’s fans, the band members themselves and literally all of Canada will surely be an emotion-laden trip across the country.

Reportedly declining to call its a farewell tour, the band along with its thousands of loyal fans from coast to coast were saddened in May when news broke of lead singer and front man Gord Downie’s diagnosis with a terminal form of brain cancer called glioblastoma multiforme.

By all accounts, Downie appeared in fine form on Friday night as he and his band played to a sold-out crowd of 9,000 adoring fans, with Downie taking only a few breaks to rest over the two-and-a-half hour show while the band played on. A tumour was discovered last December after Downie suffered a seizure, which led to surgery to remove the majority of tumour mass, followed by radiation and chemotherapy treatments.

The prognosis for glioblastoma, the most common and most aggressive form of brain cancer, is not good, with an average life expectancy of between 14 and 18 months from point of diagnosis. With less than five per cent of patients still alive at the five year mark, the disease hits two to three out of 100,000 Canadians per year, is more common in people over the age of 50 and tends to afflict men more often than women.

Below: The Tragically Hip perform “Ahead by a Century” in Victoria, July 22

The cause of glioblastoma is unknown but the disease’s pathology has been well-observed: tumours start in the connective tissue of the brain in cells called astrocytes and very quickly spread to surrounding tissue. As the tumour grows, it interferes with brain activity and, depending on its location within the brain, produces symptoms ranging from headaches and memory problems to shaking and weakness of the limbs, vomiting and seizures.

And although cancer is still the leading cause of death in Canada, cancer treatment has advanced over the past generation such that patients for all types of cancer combined have a 63 per cent of survival.

But glioblastoma’s story is different, for a number of reasons.

First and foremost, it’s cancer of the brain, the body’s most delicate and complex organ. Thus, attempts at removing the tumour – which often involves cutting out some of the surrounding tissue at the same time – inevitably leave some cancer cells behind. “Glioblastoma is often referred to as having finger-like tentacles that extend some distance from the main tumour mass into surrounding normal brain tissue,” says Dr. Stuart Pitson of the Centre for Cancer Biology at the University of South Australia. “In most cases, less than 90 per cent [of the tumour] can be removed.”

Further obstructing treatment, many chemotherapy drugs commonly used to treat cancers cannot be effectively delivered to glioblastoma tumours due to the blood-brain barrier which restricts the movement of molecules from the bloodstream into the brain. One chemo drug, temozolomide, has been shown to cross the barrier, but often glioblastoma tumours are resistant to treatment by temozolomide.

Below: The Tragically Hip perform “Little Bones” in Victoria, July 22

But research into glioblastoma has recently been pursued down a number of promising pathways.

One encouraging approach involves the use of immunotherapy, which recruits the immune system’s own antibodies to attack cancer cells based on certain protein markers on a cell’s surface called tumour-associated antigens. Recent studies are showing that glioblastoma may be treatable with immunotherapy programs involving both vaccines – including the rindopepimut vaccine which has shown to be effective in research trials – and some of the so-called checkpoint inhibitor drugs that have been shown to help shrink tumours in early-stage trials involving glioblastoma patients.

One study from the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and the University of Ottawa was the first to locate a specific protein called OSMR that is required for glioblastoma tumours to form, confirming through mouse studies that the higher the expression of OSMR proteins in mice brain tumours, the faster the progression of the disease and the quicker the death of the animal.

Researchers see the targeting of the OSMR proteins through immunotherapy as a key pathway for further investigation.

Another potentially groundbreaking line of treatment, gene therapy, is also getting more attention in glioblastoma research, involving the introduction of copies of a particular gene into tumour cells in order to negate the reproductive capacity of those cells, thereby stopping tumour growth. One gene therapy approach named VB-111 has shown to extend survival rates of glioblastoma patients on average by seven months in clinical trials.

Yet, researchers working on immunotherapy and gene therapy say that realized treatment options for patients with glioblastoma are still years away, with the recent findings providing glimmers of hope, nonetheless. Dr. Arezu Jahani-Asi, who conducted the immunotherapy study with the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, says this hope is what keeps her focused on the future.

“The fact that most patients with these brain tumours live only 16 months is just heartbreaking,” says Dr. Jahani-Asi. “Right now there is no effective treatment, and that’s what drives me to study this disease.”

Below: The Tragically Hip perform “Wheat Kings” in Victoria, July 22