Ah, off the grid living in Canada. Under the stars with not a care in the world. Uh, not quite. A woman in Nova Scotia who wants to be living off the grid has found the idea is more complicated than it might have at first seemed.

Ah, off the grid living in Canada. Under the stars with not a care in the world. Uh, not quite. A woman in Nova Scotia who wants to be living off the grid has found the idea is more complicated than it might have at first seemed.

And she’s not alone.

Cheryl Smith, who lives in Clark’s Harbour, a fishing village that is located on the southernmost point of Nova Scotia, wants to live in a modest home without electricity. But officials with Shelburne County say she needs an air exchange system and smoke detectors to meet code.

“The rules are rules, unfortunately,” says Clark’s Harbour Mayor Leigh Stoddart. “I know what she’s trying to do and I applaud her for her effort because she wants to live off the grid.”

Smith says she is baffled by the bureaucracy in her attempt to achieve off grid living.

“If what we’re trying to do is move the world into a greener place and make it more environmentally friendly so there’s something still left for our children, then why am I being forced to rely on electricity or fossil fuels if I don’t want to?” she said.

From Lasqueti Island B.C. to Bancroft, Ontario to Western Prince Edward Island thousands of people in Canada live off the grid. Most of them don’t do it because they are idealists or revolutionaries, it’s just that the place they happened to live has never been serviced.

While technology has made the idea of plopping down far from the madding crowd easier than ever, the seemingly unyielding march of red tape has moved in lockstep. In some jurisdictions, in fact, off the grid living has been made illegal.

For the increasing amount of people, however, who are seeking out the off-the-grid lifestyle, the prospect has grown tangled. While technology has made the idea of plopping down far from the madding crowd easier than ever, the seemingly unyielding march of red tape has moved in lockstep. In some jurisdictions, in fact, off the grid living has been made illegal.

Nick Rosen, author of “Off the Grid: Inside the Movement for More Space, Less Government, and True Independence in Modern America” estimates there are three-quarters of a million off-the-grid households in the United States, a number he thinks is growing at ten per cent a year. Rosen says the profile of the typical off-the-gridder has changed.

“Going off the grid is like insuring yourself against a time the lights may go out,” he told Christian Science Monitor. “In the 1970s you had a lot of old-style hermitlike survivalists. But these people are different. This isn’t the Stone Age anymore; you can live a quite comfortable life.”

While some new off-the-gridders may have been tempted by Tesla’s new $3,500 Powerwall System, the fantasy has become increasingly litigious. In Cape Coral Florida, a judge ruled that a woman, Robin Speronis, was not allowed to live on her property unless she hooked up to the city’s water supply.

A code enforcement officer declared her home uninhabitable, but only after Speronis talked about her lifestyle to a local news anchor. She said she didn’t know how the officer could have known about her living situation without entering the dwelling.

There is undoubtedly a common thread of conscious or unconscious libertarianism in many who self-identify with the movement.

In enforcing the measure, the Florida city cited the The International Property Maintenance Code, an amalgamation of three legacy codes that looked to standardize disparate regional codes and was put in place in 1997. But even the man who laid down the law in Cape Coral thinks might be in need of updating.

“Reasonableness and code requirements don’t always go hand-in-hand… given societal and technical changes that requires review of code ordinances,” Special Magistrate Harold S. Eskin, told a local paper.

Complicating things for those who want to pack up and disconnect is a dozen smaller matters, such as the prospect of insuring your home when it doesn’t comply with codes that give insurers comfort that they are making a fair bet. It seems figuring out how to be successfully living off the grid in Canada is a particularly difficult puzzle.

“If someone is living in a house with no heat and no water, that’s not somebody we would like to insure,” says Cyril Greenya of Marietta, Pennsylvania’s Donegal Insurance Group. “If they have wood fireplaces or coal stoves, that’s not something we want to insure. Now you’re talking about a fire hazard.”

Flickering just beneath the surface of many who choose to go off-grid is lingering belief that society has become increasingly conformist, if not dictatorial. You can hear it in the protests of Joe and Nicole Naugler, a Kentucky couple who had their children seized by Child Protective Services over accusations of child neglect, and in Tyler Truitt, a former marine who was warned that his house, which he outfitted with solar panels and rainwater collection systems, was condemned and he would be arrested if he tried to return to it.

There is undoubtedly a common thread of conscious or unconscious libertarianism in many who self-identify with the movement.

It makes little sense, from a planning and engineering perspective, to isolate ourselves into small, separate, fully-independent atom-like homes. It makes more sense to pool and share resources whenever possible, and to all play a fair role in doing so.

But it’s not just anti-establishment types that think a sea-change may be coming in the way a large part of society lives. It’s the other side, too.

Two years ago, the Edison Electric Institute, the trade association for shareholder-owned electric companies issued a report that warned a change in the way people view the grid may be altered a swiftly as land lines were in the face of the rise of cellphones.

“One can imagine a day when battery storage technology or micro turbines could allow customers to be electric grid independent,” said the report.

Two journalists who studied off-grid living in Canada for years came away with mixed takes on the idea. Phillip Vannini and Jonathan Taggart traveled for two years across the country, documenting the experience for a book and film. The pair talked to more than 200 off-the grid Canadians in more than 100 homes.

Vannini and Taggart found some things that surprised them: many off-the-gridders lived in suburban, not rural, areas. They were hard to categorize, demographically. The homes they lived in were overwhelmingly well-lit and heated.

But they also concluded that living off-the-grid isn’t for everyone and probably doesn’t make sense for society as a whole.

“It makes little sense, from a planning and engineering perspective, to isolate ourselves into small, separate, fully-independent atom-like homes,” they said in a piece for The Tyee. “It makes more sense to pool and share resources whenever possible, and to all play a fair role in doing so. Off-grid living can then teach us about learning that role, about what it means to do our part.”

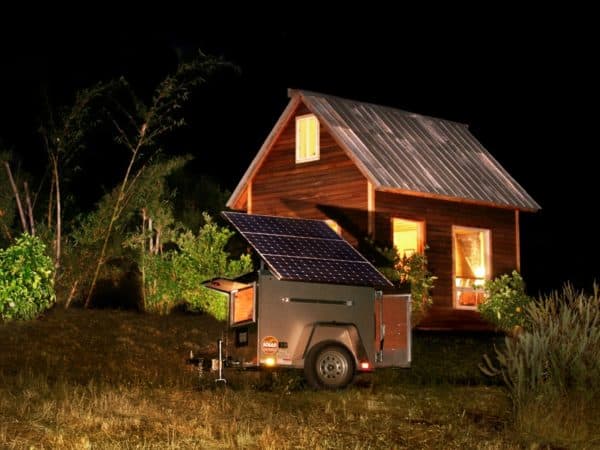

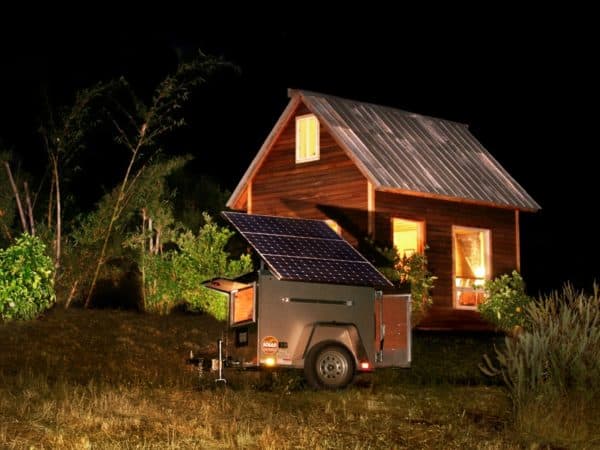

Below: Off The Grid: Living off land hour from Vancouver

Comment

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Share

Share

In addition, you can easily build a Tesla device at home that generates free electricity, I found the instructions & video proof at http://reviewcrewtv.com/how-to-create-a-tesla-free-energy-device-that-generated-free-electricity/

IM

wondering if this is why most people who build tiny homes build them as

mobile homes.. so they dont have to adhere to building code for homes?

Yes. You’re right.

Who’s rules? If people want to live off grid that’s their right. Furthermore, no one can make us be consumers either. The money parasites are just worried.

We’ve actually live off the grid here in Halifax, Nova Scotia and very much enjoy teaching other people to do the same. I’m also a military Air Force helicopter pilot which completely surprises most people. Everyone has a preconceived notion of who people are that live “off the grid”. What’s funny, is that between my day time passion of serving my country and my night time passion of promoting solar power and living off the grid… my family’s lifestyle exceeds that of 95% of the people I know. We currently have 34k fans that follow along with the build of our off grid cabin and we’ve even partnered with Elon Musk (yes, that Elon Musk) to help promote SolarCity as well as the Tesla power wall and EV. Live… is great off the grid 😉

Power, running water, working plumbing is all vanity! I live out in my Prairie Shack and everything is powered by my wood burning kitchen stove. There is nothing wrong with a hooker bath(big ol bucket of water). I boil all my clothes to wash them. Why does the government want people to have to spend all this money, to keep up with the endebted Jones?

lets remember the building code is there primarily for the safety of homeowners and linesman. If you are NOT connected to the grid then there goes half the purpose of the code. Lastly, off gridders work with a lot less amperage then being connected to the grid, thus leaving the other half of the purpose to be deemed unreasonable. Since the simplicity of our systems and pretty much anyone with the will to go off grid, also holds the will to learn and succeed. I just want to make note that the answer to your question is simply put, yes. However it is not at all intended to circumvent the safety aspect, but only to give us the little remaining freedom we have left.

We learn from each other !

The link you provided doesn’t work.

I have a friend that has a house just a short distance from Markdale,ON. He is charged a delivery fee from Hydro One even tho he isn’t connected to the grid. The fee he pays is based on what others pay in the area that are on the grid. So much for not being connected.

To collect taxes!

Because this Criminal Libtard Government of Ontario has no problem committing fraud!!!

It used to be for safety of homeowners, now it’s another f’ing revenue tool for Governments!

The title is ludicrous. Does anyone actually believe that people might not have the ‘right’ to live off grid? That we are legally required to be in debt to a power company? Seriously? People are naturally free, sovereign beings. We have to get our heads clear of the idea that anyone has more rights than anyone else, and that includes so-called lawmakers telling us how and where we have the ‘right’ to live.

If I could afford a house in southern Ontario, I would verify that I could live off the grid before buying. That said the Tesla PowerWall looks like a interesting idea.

On a side note you can have a PW setup and only recharges your batteries during the low cost time frame, and use that stored energy during the high cost time frame if you need.

Just don’t pay. What are they going to do? Cut off your electricity. The only rights you have are the one’s you don’t let “them” take away.

Reasonableness and code requirements don’t always go hand-in-hand…

Actually it’s more like common sense which for the most part has been bred out of most .

Should Canadians have the right to live off the grid..??? I believe the more pertinent question would be: Does the government have the right to force people to stay connected

to the grid? The government which, by the way, is there to do the

bidding of its people, not the opposite way around. For the record, I’ll be off the grid at some point in the not-too-far-off future, and they can f*** their hat. 🙂

Do you have a Facebook site, Steve?

Never mind….found ya! 🙂

the same issues in America as well. i’ve read a number of articles/reports about how ppl are being fined for collecting rainwater and ordered to remove collection materials. same is true for ppl who have made ponds on their property.

Should politicians and regulators have a right to have access to the grid?

Are we government assets or free humans??

weve been off grid for 3 years now and i love it. no one has ever given us flak for not being hardwired into the system we haul our water from town in winter or from the lake in summer. what little power we do use comes from a solar panel. and believe it or not we have a smoke detector ( they still make battery operated ones ) and a fire extinguisher both in our home.

CODES are not for living breathing human beings however. Does the jackass care to explain that?

I respect your ability and choice to live off the grid but you do know you’re not serving anyone in the military but the elite right? And that service is what makes living off the grid harder and harder, because once all opposition is gone (and the military helps eliminate that opposition) then they will turn their focus onto the one remaining free peoples, the domestic off gridders.

This is the same thing they are doing to us south of your border.

Two things…

1. I can tell you’ve never laced up a pair of boots, picked up a weapon, and put other people lives before yours. Think twice before you point a finger at a military officer and tell them what and who they are and are not serving. You’ve got it completely backwards and it’s painfully clear to anyone reading your comment.

2. I’ve looked over your other comments and you post with the same lacklustre negative distain every single time. The real problem… is in your own belief in yourself. It’s lacking. Again… crystal clear.

If your not happy living in your skin then do something about it. But crying foul and whining about other people who sacrifice themselves to provide people like you the freedom to speak your mind… sometimes I have to remind my daughter that I leave her behind for months at a time to fight for people like you to have what you do.

Sometimes… I really have to ask myself if it’s worth it reading comments like yours.

Enjoy your freedom.

Clearly you enjoy being condescending so much that you cannot resist.

Enjoy your smugness looking out judging the world from your own

glass house.

(btw sarcasm fizzles when grammar fails)

and yet the article clearly shows you two individuals who are not allowed

to move into their homes unless hook up (electric for one; water for the other)

is complete.

So, their “right” is being squashed.

Duhhhhhhhhh, you can live off the grid with smoke detectors and an air exchanger……holy crap batman…… !!!!!!!!!

Living off the grid should be covered under freedom of religion. Sad that this Canadian lady would have to use a loophole like this but all these scriptures were written off grid and she could use them.

There are Mennonites all over Southern Ontario. Is the government going to force them to use electricity? They are still allowed to ride a horse and buggy on major streets. The vast majority of people here appreciate their simple lifestyle We buy their awesome goods and would never say they should be forced to have electricity.

To get your Ontario drivers license you need to learn how to treat horse drawn buggies on the road. Where do I get tested for my ability to control a horse drawn buggy? Hope they don’t test the horse for emissions.

http://www.mto.gov.on.ca/english/dandv/driver/handbook/section2.3.7.shtml

The law that requires people to have an electric smoke detector, electricity and a ventilation system were intended for people who rent out property and new home builders.

This should be an easy law to amend. Almost all Canadian citizens would agree living off the grid, in an appropriate area is none of the government’s business.