On the ninth floor of SAP Canada’s Montreal headquarters, Hervé Pluche outlines the challenges inherent to effective one-to-one mobile marketing: “When we have access to so much data, the main challenge is no longer to extract insights, it’s to ask the right question,” he says.

Pluche, SAP’s global vice-president for Precision Marketing, is describing his work on Merci, an iOS app built in collaboration with Montreal’s Société de transport de Montréal (STM), beta launched last May and now set for mass rollout.

Having access to too much data is the kind of problem that most marketing people wish they had, never mind puzzling through the even steeper challenge of interpretation. While most marketers have been struggling with simply comprehending the implications of Big Data for instant-response, precision marketing, Pluche and his colleagues have been parsing a steady stream of real-time mobile consumer data for several months now, and seem finally to be getting to grips with what it means and how best to harness that data for marketing purposes.

“I think we have enough to say that, through work we’ve done around that use-case, we’ve basically changed by an order of magnitude the response of the consumer, compared to a well-known channel, which is the web. So from web to real-time mobile, personalized, if you take those metrics on the web, times ten is basically what we’ve achieved with this new channel.”

Times ten. Most online marketing, even effective online marketing, is still straining to break through single digit territory with regard to click-through rates, never mind conversion (the moment when a user accepts and acts on an offer). Even then, most people who click on banner ads do so by accident. So those numbers are likely too high. What has SAP done to adjust the stakes?

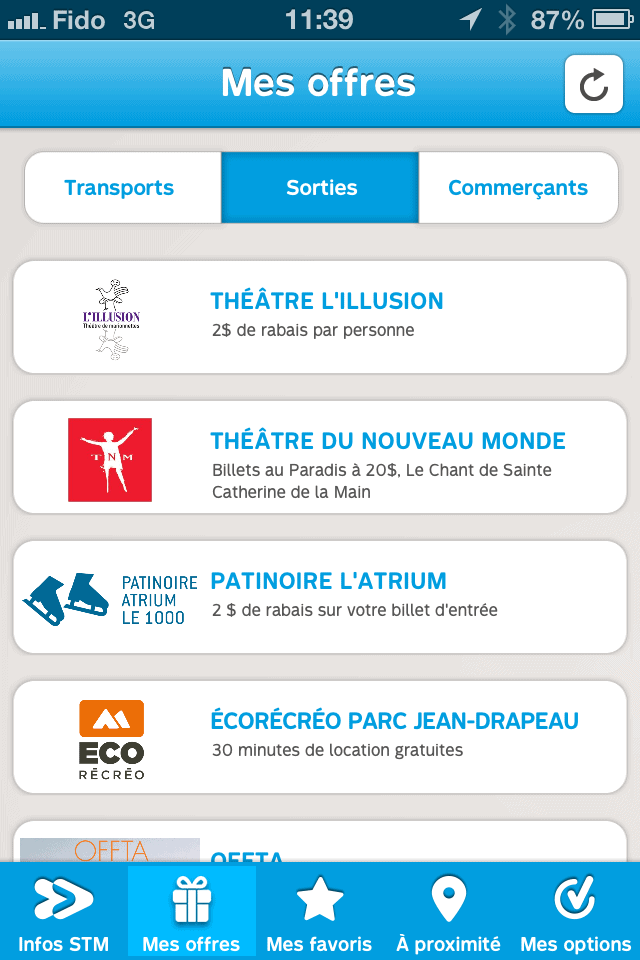

The Merci app contains offers ranging from discounts on transportation, such as the Bixi bikeshare service, to outings and retail offers aimed exclusively at the STM ridership.

Pluche is effusive about the results of his experience with the Merci app so far. “STM was serious about putting the consumer at the centre of a new experience. It’s consumer-centric. It’s not doing business the good old way. It’s really exploring a new way of thinking and strengthening the relationship with the consumer, making sure that it’s a win-win relationship.”

The app is essentially a location-based loyalty program, and is separate from the STM’s main app which is dedicated simply to getting from Point A to Point B. The Merci app contains offers ranging from discounts on transportation, such as the Bixi bikeshare service, to outings and retail offers aimed exclusively at the STM ridership.

A few years ago, the STM implemented a scan-and-go card for riders called Opus, which personalizes the public transportation experience to the extent that the cards collect insights about the STM’s 2.5 million cardholders that weren’t available when the most complicated data that they had been gathering was how many times a turnstile clicked during a day.

Pierre Bourbonnière, director of marketing for the STM, comes from the loyalty program world, his previous history being with Air Canada’s Aeroplan program. His job for the last six years at the STM has been to unlock the potential of the Opus card in a way that a standard loyalty program could not. “The world doesn’t need another loyalty program, with points and cards in your wallet. PanAm started doing this about 30 years ago. Let’s move on.”

To accomplish this, he turned to SAP. “What we’re doing here is one of the first marketing tools that ensures that we have the right product and the right service to the right customer at the right time in the right place. Geolocation and notifications, when you receive them, if they are really relevant, people will open them.”

The Merci app is not only a loyalty program offered by a local transportation service to its customers, but also by extension a loyalty program that each business participating in the app could not conceivably have built on their own. And the more businesses participate in the app, the more precise the self-learning algorithms built to model consumer behaviour become.

Bourbonnière’s data affirms Pluche’s assertions about the app’s efficacy. “The ten best offers converted at 64%. 25% of the offers that were most popular generated a 44% conversion rate. 18% generated a 100% conversion rate. And 10% generated no conversion whatsoever.”

When you have a conversion rate between half and two-thirds, whatever the context, you’re doing something right.

“We’ve got about 340 partners that are in the retail business, and close to 1,000 partners who are in the event business. Anything that moves in Montreal, from hockey games to theatre to opera, is basically part of this program,” says Bourbonnière.

La Vitrine, the central ticket hub for over 500 festival, museum, theatre and concert venues, supplies approximately 85% of the content in the app’s Outings section (basically all of the non-sports related events), which makes for a fairly hefty concentration of highbrow cultural offerings.

While some of the app’s offers seem a little tenuous, one uncontested gem is a 25% across the board discount on tickets for Orléans Express, the regional bus carrier. Such a steep discount is evidently merited by the increased insight into customer behaviour that would ordinarily be difficult to access, says Marc-André Varin, Vice-President of Business Development, Marketing and Communication for Keolis Canada, the company that runs Orléans.

“Beyond just the discount, obviously, it’s having access to this database of clients and being able to communicate with them and establishing a relationship with those clients. Obviously, that’s the key tool we want to use. From the platform, the people are invited to put in their email address and answer a couple of questions, and then they receive a promotional code that they use on our website to get their 25% discount. And the response has been pretty good.”

Getting here hasn’t been easy. The app has been in development, off and on, for three years. For Pluche and SAP, the stakes are high. “We had 9 offices around the world contribute to this initiative. 9 offices, 70 developers, from Bangalore, Palo Alto, Vancouver, Montreal, Boston, Paris, Walldorf, Tel Aviv. We had to source the expertise globally. Imagine the challenge for a company like STM, which is not a software developer, to assemble that end-to-end solution. They would have to hire 100 people, full-time. This is not within reach of a start-up.”

“Quebec is probably the strictest area in North America, next to Germany, in the world, in terms of privacy,” says Bourbonnière. “And how do we satisfy our lawyers, meet the legal requirements of the province of Quebec? That was a major challenge.”

And then there’s privacy. The privacy issues inherent to a public-private partnership of this scale ate up a fair chunk of that three years, too. Then again, three years later, the privacy concerns around an app that not only knows your every move but also guesses where you’re likely to be at a given time of day while also trying to sell you things have been hammered out approximately as thoroughly as they’re ever likely to be, through extended sessions involving several gangs of lawyers.

“Quebec is probably the strictest area in North America, next to Germany, in the world, in terms of privacy,” says Bourbonnière. “And how do we satisfy our lawyers, meet the legal requirements of the province of Quebec? That was a major challenge.”

Ultimately, the way this was accomplished was to break the data sets relating to each user into two separately stored chunks: mission critical data relevant to public transit (fares, use habits, etc.), and personal information. The first set is kept locally and the other in SAP’s server in Walldorf, Germany. Separately, the two datasets can’t identify an individual user, until the moment they click “accept” on a specific offer. Then the relevant pieces come together, rather like a marketing version of the Large Hadron Collider.

For Pluche, this approach was both legally necessary, and a matter of responsibility.

“The idea of breaking down information into two separate silos that can be combined only when the consumer initiates a session, with no latency of information once the session is complete, is the key to what we’ve done to comply with privacy regulations, and meet the consumer expectation in terms of visibility and control, and deliver the benefit of personalisation that requires that I also have access to as much information as I can.”

And what of the merchants themselves, whose main hope for participation in the app is to increase their business through proximity to a customer base they were previously unable to tap? Alex Sereno of Café Barista, a B2B espresso coffee roaster with no physical retail space, points to the power of geolocation combined with the app’s ability to target offers, aimed at a specific user at a specific time of day, as its differentiating feature. “You get out of the metro station, you get out of the bus, boom, you’ve got an offer. Why not take it?”

Café Barista’s strategy so far has involved the use of promo code discounts offered through its online boutique. He says he’s seen a good return on his participation so far. “It’s cool,” he says, “because it’s a physical event with a virtual tool. To me, that’s the future.”

Now, if the STM could fold the city’s recently launched food truck program into the app, we’d have world peace.

___________

Comment

One thought on “Montreal’s Transit System Tries to Get Smart”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Share

Share

Ironically, there is no mobile connection in most of STM’s subway network.